Princeton Geniza Project Datasets

“Then we boarded a boat that contained not a single nail of iron, may God protect us with his shield…”

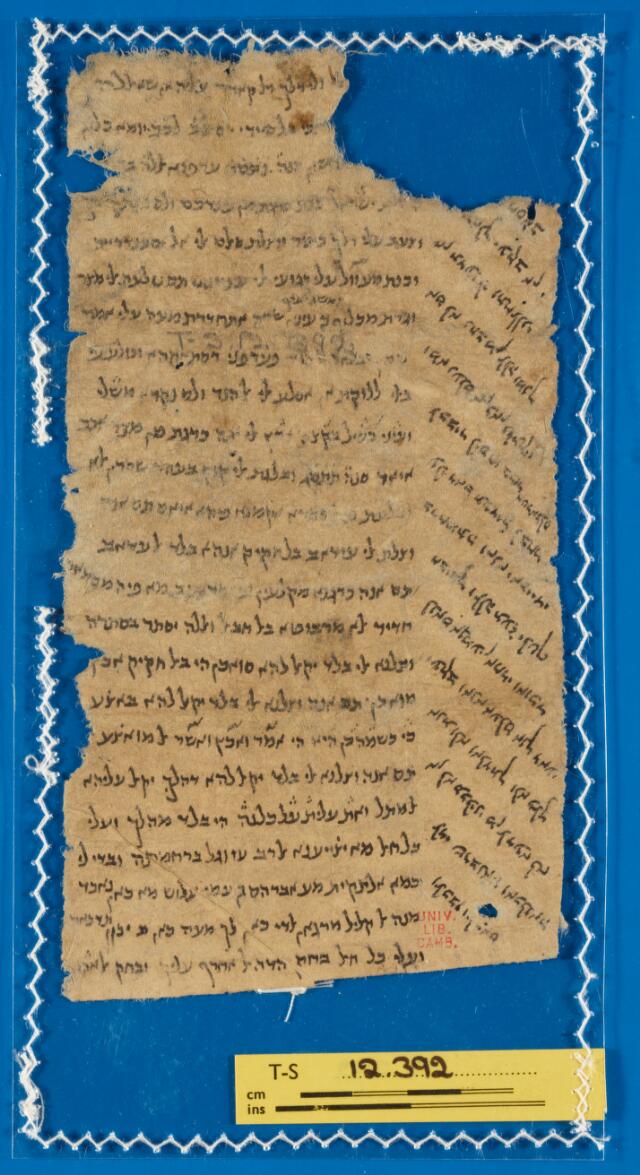

T-S 12.392

https://geniza.princeton.edu/documents/9690/

From a translation by Marina Rustow and Alan Elbaum. Image provided by Cambridge University Library.

“Then we boarded a boat that contained not a single nail of iron, may God protect us with his shield…”

Thus wrote a Libyan Jewish trader in 1103 to his brother-in-law back home. He had made it as far as Dahlak, an island in the southern Red Sea, but most of his voyage still lay before him: like many northern Africans of his generation, he hoped to make it across the Indian Ocean to the Malabar coast, where he would trade flax or other Egyptian commodities for pepper and other commodities from India and farther east. Having made it up the Nile, across Egypt’s eastern desert and as far south as Dahlak, the new obstacle now before him was a type of craft he’d never seen before: one whose planks were tied together with ropes made of coconut coir. Little did he know, this was a perfectly safe way to travel; boats of this kind had been utilizing the regularity of the monsoon winds to ferrying humans across the Indian Ocean since the days of the Roman emperor Nero.

The Cairo Geniza

The richness and detail of his story are known to us thanks to an extraordinary cache of historical sources: the Cairo Geniza, one of the densest and most coherent corpora for premodern history. Preserved in a medieval Egyptian synagogue, geniza sources were made available to scholars in the late nineteenth century and have not yet been completely cataloged, let alone published or translated. The texts are in a diverse array of medieval languages and dialects, among them Arabic written in Hebrew characters (known among modern specialists as Judaeo-Arabic).

Many of the texts are fragmentary—chunks or pages of books too worn out to be read, and so deposited in a dedicated chamber in the Ben Ezra synagogue in Cairo. Among those hundreds of thousands of book fragments, however, there are also more than 30,000 documents: letters, lists, accounts, legal deeds, doodles, amulets and other kinds of ephemera their owners never intended for decipherment by dogged scholars hundreds of years in the future. The world of the geniza, though centered on Egypt, stretches from Spain to Sumatra thanks to the travels of long-distance traders such as our Libyan with the transportation dilemma.

The Princeton Geniza Project

The sheer volume of information geniza sources offer is uncommon in premodern history. But precisely this abundance — and the fact that the sources are often torn, incomplete and linguistically recondite — makes special demands of scholars. Early in the personal computing era, a Princeton-based team therefore began digitizing them. Thus the Princeton Geniza Project was born: a database devoted to the documentary sources of the Cairo Geniza. As the project marked its thirty-fifth anniversary, the authors launched a major overhaul of the database.

The Princeton Geniza Project (hereafter PGP) is a long-running project, dating back to the 1980s, but this is the first time comprehensive data from the project have been published as a dataset for external use separate from the various web interfaces for accessing geniza materials. This essay accompanies our first published dataset. Our intent with this article is to provide sufficient historical context on the project for researchers to understand the nuances and unevenness of the data, to serve as a reference for those who want to work with the data, and to offer provocations and inspirations for the new research that is enabled by making the information and content from PGP available in a new form.

PGP version 4.x

The Princeton Geniza Project (PGP) is a product of decades of scholarship and with multiple different custodians and changing leadership. We determined that the current incarnation of the project, which was launched in 2022, should be labeled version 4 (hereafter PGPv4), as an acknowledgement of the long history of this research project, dating back to a CD-ROM version published in the 1980s.

This new version was an overhaul of PGP data and re-envisioning of PGP interfaces, both public and curatorial. Our goals were to modernize and update the project infrastructure, connect disparate pockets of data, and make it easier for project team members and researchers to manage and work with the data. We worked to model and aggregate data sources that were previously siloed and managed in different ways and places, sometimes with only one or two people who had access and knowledge to make updates. Adding new transcriptions was a particular pain point motivating this rebuild, but before we could address that problem we needed to revisit the data infrastructure for the geniza materials at a higher level.