AudioVisual Data in DH

Introduction: Special Issue on AudioVisual Data in DH

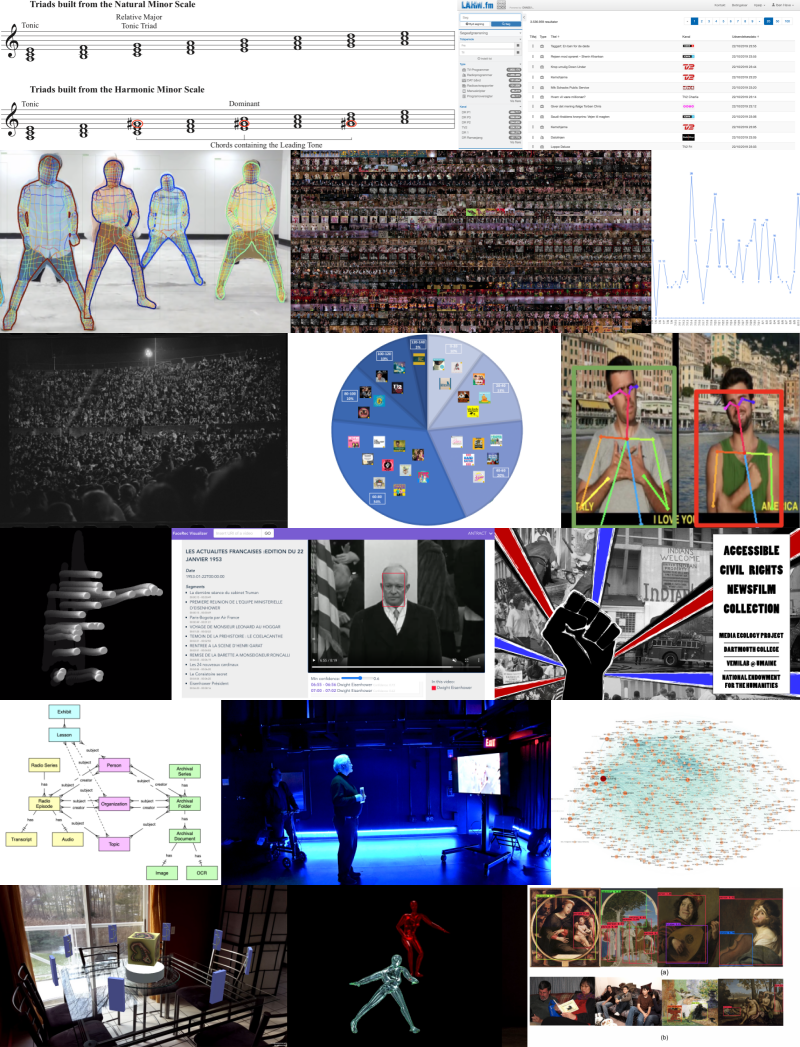

A mosaic of article figures included in the special issue.

Towards AV DH

Many scholars have repeatedly demonstrated how expanding our areas of inquiry builds new routes for the field 1 2. Yet, often those interested in working with AV data have found themselves swimming upstream. Text and word culture have enjoyed a dominant position in DH, bolstered by factors such as the prominence of text analysis and the form of academic journals 3 4.5 Replicating the larger structures of higher education, racialized and gendered beliefs about what counts as “rigorous” scholarship that marginalize fields such as cultural studies and visual culture studies also permeate DH and further explain why text (analysis) has enjoyed a privileged position along with their related academic fields 6.7 However, exciting developments are continuing to support and amplify the work of AV data in DH.

One of those developments is shifts in technology. The ability for computers to create, “read”, and store AV data followed by advances in areas such as machine learning have augmented computational image and sound analysis. Pioneering approaches such as cinemetrics that once relied on hand coding and text-based annotations can now be automated. Within DH, this has led to new theories and methods such as cultural analytics, distant listening, and distant viewing 8 9 10. These developments have led scholars such as Melvin Wevers and Thomas Smits 11 to argue that DH is seeing a “visual, digital turn”. Meanwhile, Mary Caton Lingold, Darren Mueller and Whitney Trettien 12, in the edited volume Digital Sounds Studies , demonstrate how pairing digital tools with “interpretive practices that always attend to the human” forges new paths for sound studies and DH.

Another critical development is digital access to AV materials. As DH scholars increasingly think of their sources as data, they have benefited from large-scale digitization of audiovisual collections.13 At the forefront over the last three decades have been governmental and GLAM (gallery, libraries, archives, museums) institutions around the world to digitize collections, whose initiatives have often been spurred by deteriorating physical collections.14 With millions of items digitized, platforms were funded by cultural, government, and scientific organisations for providing access to audiovisual heritage collections alongside the emergence of platforms by for-profit multinational corporations, all of which enabled the circulation of digitized and digital-born materials online.15 While issues such as copyright and funding still loom large, DH scholars have greatly benefited from the significant investment in digitization over the last 30 years.

Finally, we turn to institutional developments.16 Along with conferences specifically dedicated to DH and media [e.g. Transformations Conference], new journals have developed such as the International Journal of Digital Art History and Journal of Cultural Analytics featuring scholarship at the intersection of AV research and DH.17 In order to further amplify AV work in DH, colleagues worked to develop a Special Interest Group (SIG) within the Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations (ADHO). The AudioVisual in DH (AVinDH) SIG was proposed after a successful workshop on how to integrate the Audiovisual in the Digital Humanities in Lausanne at DH2014, and formalized a year later at DH2015 in Melbourne. One result of the SIG’s work is this special issue.18

New pathways are bringing about exciting opportunities in DH as exemplified by the articles in this issue. They model how AV research can be the subject of analysis (e.g. film) or result of analysis (e.g. podcast). They highlight less visible humanities disciplines in the DH, model the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration across institutional structures, demonstrate how cutting edge scholarship comes from a plethora of positions, and offer new questions that the field is only beginning to grapple with. The contributors’ model paths for constructing entry points, building bridges, or adding intersections for engaging with audiovisual in the digital humanities. Amplifying the work of scholars with a range of disciplinary, institutional, and political commitments, the special issue constructs a more capacious configuration of DH.

Contributions

The special issue is organized into five sections. The first focuses on annotation of AV material as method and theory. The second explores analyzing (meta)data, which often includes annotation, to build and analyze AV corpora. The third focuses on creative and liberatory ways to remix AV (meta)data as a way to innovate pedagogically and methodologically while furthering discipline specific interventions. The fourth dives further into computational methods, particularly machine learning, in turn demonstrating how DH is reconfiguring these methods and ways of knowing to answer humanities questions. The special issue ends with a focus on how AV forms such as podcasts and film can also be the form of scholarly knowledge in the field, highlighting how form and argument can be mutually constituted.

Next, we turn to the contributions that comprise each section. The first explores annotation as a powerful way to add context and analyze AV data. A particularly prominent area of such work has been in film studies. Therefore, the first three articles offer a snapshot of different approaches and tools for film annotation. Cooper, Nascimento and Francis present their KinoLab and discuss the opportunities and challenges of Omeka for narrative film language analysis, including the challenges related to copyrights. They argue for a universally accepted data model for film analysis. We then turn to a new annotation platform called Mediate built by a team at the University of Rochester. Burges et al. discuss how they use the annotation tool in the classroom in three different disciplines - film and media studies, music history, and linguistics - and introduce the concept of “audiovisualities” as a theoretical frame for understanding remediation through annotation. Next, Williams and Bell discuss how the Media Ecology Project is conceived as a virtuous cycle and incubator working to increase access and discovery of moving images, with a particular focus on tools such as the Semantic Annotation Tool. Zooming out, Clement and Fisher theorize a new approach to annotation. They bring together sound and literary studies to introduce the concept of “audiation” as a framework for audiated annotations that increase access and discovery.

The next section focuses on how (meta)data can open up analytical possibilities. Using metadata to reunite AV materials, Sapienza et al. describe the process of reuniting radio and text files virtually that belong together but ended up at different institutions. After discussing why audiovisual collections in general are heavily under described, they describe how virtual reunification and integrated access was realized through the use of linked data, minimal computing, and synced transcripts. Next, Hoyt et al. discuss the analytical possibilities afforded by metadata. Focused on podcasting, they discuss three different methods for studying RSS feeds and podcast metadata, and point at the specificities of methods for born-digital media vis-à-vis digitized media. Carrivé et al. then focus on the first development phase of their ANTRACT project for the transdisciplinary content analysis of 1262 newsreels containing more than 20,000 French news reports. They discuss how they dealt with the project’s main technological challenge to process data and build tools to familiarize historians with the automated research of large audiovisual corpora in order to then use the data to pursue inquiry about Les Actualités Françaises news reports. Finally, Gienapp et al. show what can be done when data is brought together from different sources to analyze music collaboration. They demonstrate how network analysis can reveal the contours of collaboration among musicians.

In the third section, the authors creatively (re)mix AV data with a focus on audio data. Using audio data, Tyechia and Carrera demonstrate how centering Afrofuturism in DH pedagogy through mixtapes can not only realize the goals of an undergraduate composition course but realize a liberatory DH praxis. Bonnett et al. combine data art, landscape art and augmented reality in their DataScapes Project. Departing from the premise that data can be translated into visual and sonic forms, they use protein data and texts from the bible, turn them into sequences, and translate these into visualisations and compositions. Kramer then asks what if we listened to images. Building off of previous work on “image sonification”, he argues that transforming the visual into audio opens up new ways of seeing and hearing the past. Next, Have and Enevoldsen demonstrate how toggling from close to distant listening offers insights about the longue durée of Danish radio content by scrutinizing what is audible with the human ear and searching for patterns using AI. Next, we turn to work that makes field specific interventions. Martin constructs a new path for listening to gentrification in Washington DC by combining ethnography, passive acoustic recording, and computational sound studies. The work also demonstrates how centering Black DH offers new ways to understand the relationship between embodied and computational audio analysis in DH, in turn forging new liberatory possibilities for the field.

The next section continues with the application and reconfiguration of computational techniques, particularly machine learning, to conduct data analysis on large collections of AV data. Looking at a large collection of artwork showcasing musical instruments, Sabatelli et al. introduce the usage of computer vision techniques to automatically locate musical instruments in images. They investigate the algorithmic properties of their analysis and show how it leads to innovative scholarship in music iconography. A paper by Lupker and Turkel illustrates the potential of investigating novel intersections between research in the humanities by using musical theory to guide the training and usage of machine-learning algorithms applied to a large corpus of digitized music. A born-digital collection of K-pop dance videos hosted on YouTube is analyzed using state-of-the-art computer vision techniques in a paper by Broadwell and Tangherlini. Their article develops a typography for describing and analyzing poses and choreography to facilitate the data-driven analysis of time-based media. Oyallon-Koloski et al. present a different approach to the study of movement in space by showing how motion capture technology can be used within film, dance, and movement studies. As with the Lupker and Turkel article, Oyallon-Koloski et al. illustrate the novel integration of theoretical frames from the humanities – in their case, Laban Movement Analysis and Bartenieff Fundamentals and Movement Studies – and the usage of computational techniques. In another take on the detection of bodies moving in space, Fragkiadakis et al. introduce an automatic system and taxonomy for tagging and describing digital videos of sign-language usage. Together, these articles illustrate the potential for work in AV DH to infuse machine learning with analytical commitments from the humanities.

Finally, we turn to articles that use DH to push the boundaries of form for scholarly knowledge. In order to demonstrate how the podcast format expands our definitions of text, Edwards and Hershkowitz reveal how podcasts can realize intersectional feminist approaches to DH. Along with demonstrating and discussing the creation of the Books Aren’t Dead (BAD) podcast in the article, they discuss the process in a podcast for this special issue. Kim then explores how motion caption and virtual reality can be used to record and visualize movement histories as a form of cultural heritage preservation. Through these forms, one can then use visual storytelling, she argues, to demonstrate how movement, dance, and ritual cannot be separated from a person’s personal narration of the experience. Finally, Mittel’s contribution showcases twenty audiovisual deformations of the classic musical “Singin in the Rain” in still image, GIF, and video formats. The essay considers both what each new deformation reveals about the film and the way we engage with the by algorithmic practices derived object as a product of the “deformed humanities.”

The invitation of the authors in this special issue to think about the relationship between form and argument is one we also embraced. The publication needs, some of which weren’t possible, of our special issue pushed the boundaries of the form and format of DHQ as a journal that is catered for linear reading of articles as written texts in XML. As a result, the articles in this special issue include 5 sound files, 52 embedded videos, and 176 gifs and images. These AV components are key elements of the authors’ argumentation. The special issue attempts to more closely mirror how scholars of AV materials in DH actually produce and create scholarship. In this context we take as a guide other pioneering initiatives in this field such as Scalar, VIEW journal, Audiovisualcy, and [in]transition that question the relation between the affordances of a publication platform and the interactivity and multimodality of scholarship that increasingly embraces creative modes of production. We hope that these incremental steps within DHQ can forge exciting new possibilities for the field.

Finally, our decision to partner together to co-edit was driven by features of AV work in DH. First, our own areas of expertise – statistics and digital images, history and audio, american studies and photography, and media studies, television & film – reflect a range of audio and visual scholarship that animates DH. Second, the inclusion of a colleague housed in a Math & Computer Science department, Tayor Arnold, demonstrates how digital humanities scholarship often requires working with and giving proper credit to experts trained in computational fields. Third, we wanted to build collaborations across geopolitical boundaries and languages that might help us think critically and beyond the particular configurations of DH that shape our local, regional, or national context. We recognize that our positionalities as White able-bodied scholars living in the global west and north also brings limits. As a part of our efforts, we paid special attention to circulating the CFP beyond our immediate DH circles with particular attention to reaching beyond the US and Western Europe. However, there is still more work to do. Yet, we do hope that the issue in aggregate reveals how thinking across disciplinary, cultural, and spatial boundaries enables a more capacious configuration of the field than currently articulated.

Conclusion

As we look toward the future, we are enthused about the possibilities and realistic about the challenges. Along with the work featured in this special issue, areas such as 3D, AR/VR, and game studies are forging exciting paths. As disciplines (albeit slowly) adopt more capacious guidelines for what counts, forms of scholarship such as films, multimodal digital projects, podcasts, and software are receiving well overdue credit. Because of the teamwork and expertise often required to access and work with AV data, this area of DH also pushes us to work across ossified divisions such as the “Humanities” and “Sciences”, “faculty” and “staff”, and “university” and “cultural institution” in ways that can help us realize a more collaborative, equitable, and generous configuration of the field.19

At the same time, challenges remain. There are major obstacles to working with AV. For example, digitized images have significantly larger file sizes than textual data making them hard to transfer and process even in light of recent technological advances 20. This makes computational analysis of large collections of digitized visual materials difficult for institutions that do not have access to extensive computational resources. Audiovisual materials are also often subject to varying degrees of copyright and access restrictions, dictated often by large multimedia producers 21. This makes it relatively difficult to work with certain collections, such as television news programs and feature films, and risks limiting the kinds of work with which digital humanists can work. Even when we do have access, the scale of AV data is growing rapidly, particularly given the rise of born digital AV content, and with this comes implications for how and who is positioned to analyze these materials. Existing audiovisual archives are heavily skewed towards European- and U.S.-centric collections. As we work through these challenges and opportunities, we need to continue to listen and engage with the cautions and critiques about computation and algorithms from scholars such as dana boyd and Kate Crawford 22, Ruha Benjamin 23, Jessica Marie Johnson 24, Catherine d’Ignazio and Lauren Klein 25, and Safiya U. Noble 26.

Finally, we want to thank the contributors, reviewers, and DHQ, specifically Managing Editor Cassandra Cloutier, for their work. Even under what were once “normal” conditions, writing an essay for publication is demanding. The challenges quickly mounted as authors revised amidst a global pandemic that disrupted everyone’s daily lives and affected communities unequally due to structural inequalities. As authors and our colleagues at DHQ tried to balance caregiving, jobs, and their own health, among other duties, they still carved out time to make this issue possible. This is quite an achievement, and for which we are grateful. Finally, we want to leave with an invitation. We encourage readers interested in continuing to further engage with AVinDH to join the SIG. We look forward to all that lies ahead.

McPherson, T. “Introduction: Media Studies and the Digital Humanities” Cinema Journal 48, 2: pp. 119-123 (2009). ↩︎

Manovich, L. The Language of New Media , Cambridge MA: MIT Press (2002). ↩︎

Svensson P. “Humanities computing as digital humanities” Digital Humanities Quarterly , 3, 3 (2009). ↩︎

Sula, S.A. and Hill, H.V. “The early history of digital humanities: An analysis of Computers and the Humanities (1966–2004) and Literary and Linguistic Computing (1986–2004)” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities , 34, 1: pp. i190–i206 (2019), https://doi.org/10.1093/llc/fqz072. ↩︎

For data about the focus on text analysis and increased presence of AV, see 27 as well as Weingart’s blog posts about the ADHO conference. For a list of analysis and data about DH conferences and journals from DH scholars, also see Weingart’s list on his blog ↩︎

Losh, E., and Wernimont, J. (Eds.) Bodies of Information: Intersectional Feminism and the Digital Humanities , Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press (2018). ↩︎

For example, efforts to frame computational text analysis as more rigorous and hard in part based on claims to the use of scientific methods has asserted problematic hierarchies of knowledge production in the field. It is not a coincidence that the field has been slow to acknowledge and engage with the work of humanities fields that have been feminized and racialized. Scholars from these fields have long proven how ways of knowing - such as affective, aural, embodied, and performative, and visual - may actually be the only way to recover the pasts that constitute (and often haunt) our present and through which we can imagine new futures. The work of scholars such as Kim Gallon 28, Safija U. Noble 29, Amanda Phillips 30, Roopika Risam 31, and Puthiya Purayil Sneha 32 to center BlackDH, postcolonial DH, and #transformDH has made important space to think about other forms of knowledge. ↩︎

Manovich, L. Cultural Analytics , Cambridge MA: MIT Press (2020). ↩︎

Clement, T. “Distant listening or playing visualisations pleasantly with the eyes and ears” Digital Studies/Le champ numérique , 3, 2 (2013). ↩︎

Arnold, T. and Tilton, L. “Distant Viewing: Analysing large visual corpora” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities , 34, 1 (2019): pp. i3-i16. ↩︎

Wevers, M. and Smits, T. “The visual digital turn: Using neural networks to study historical images” Digital Scholarship in the Humanities , 35, 1: pp. 194–207 (2020). ↩︎

Lingold, M. C., Mueller, D. and Trettien, W. (eds), Digital Sound Studies. Durham , London: Duke University Press (2018). ↩︎

The transformation is quite impressive if we look back to Miriam’s Posner’s article on the term “humanities data” 33. Posner notes that this is an unusual term for humanities scholars. Fast forward five year and it is increasingly common to hear materials such as books, films, and photo called data. ↩︎

We give some examples of digitization initiatives from around the globe for further reading. A number of initiatives across Asia and the Pacific are mentioned in a report about digitization of Indian cultural heritage at the Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Art 34, a centre which itself has digitized a considerable proportion of its heritage resources, and made them available through its website. Other initiatives mentioned in the report are a.o. 35, 36, and 37. When considering Africa, a special issue on the impact of digitization and new media on various African societies in the Journal of Eastern African Studies sheds light on how in this part of the world the digital transformation primarily manifests itself by the uptake of social media 38. Classical ancient works are digitized in Egypt, at the remake of the ancient Library of Alexandria, the Bibliotheca Alexandrina that can be found in present day Alexandria. In a report published by the Unesco on digital culture in Spanish speaking countries 39, the core initiatives are investments in infrastructure to decrease the digital divide within the countries. In the US, the Federal Agencies Digital Guidelines Initiative FADGI established guidelines for digitization in 2007, enabling standardized digitization of cultural heritage collections by archives, museums and libraries. For more information about the EU’s work, see 40. Given the important calls for a postcolonial DH, it is worth noting that ideas of nation and nation building are inextricably linked to many of these initiatives. Such work can be a colonial project as well as a form of resistance and decolonization. What gets digitized and by whom is a complicated, and often fraught, process, see 41 42 43. ↩︎

For example, an early European initiative was Video Active, the predecessor of EUscreen and EUscreenXL, currently consisting of 31 organisations from 22 European countries who have come together to increase access to their materials. Together with the increased availability of digitized materials, the launch of user-generated content platforms such as YouTube in 2005 and SoundCloud in 2007 enabled the circulation of digitized and digital-born materials online. ↩︎

We find Jessica Marie Johnson’s naming “the digital humanities in its most structural form as articulated by global academic institutions” as “DHDH” to be a helpful configuration 24 ↩︎

Indeed, parallel to this evolution, media studies and other humanities journals started to pay attention to multimedia data as a new presentation form, often in an open access format, such as Vectors. In history, sound studies musicology we notice similar initiatives such as the International Journal of Digital Art . ↩︎

To read more about the founding, please see our interview with the SIG’s founders. Notably, in 2016, a SIG for Digital Humanities and Videographic Criticism was founded within the Society for Cinema and Media Studies, the largest association for film and television scholars in the world. ↩︎

Simoncelli, E. P. “Statistical models for images: Compression, restoration and synthesis” Conference Record of the Thirty-First Asilomar Conference on Signals, Systems and Computers, 1: pp. 673-678 (1997). ↩︎

Menell, P. S. “Envisioning Copyright Law’s Digital Future” NYL Sch. L. Rev ., 46: pp. 63-199 (2002). ↩︎

boyd, d. and Crawford, K. “Critical questions for big data” Information, Communication & Society , 15, 5 (2012): pp. 662-67. ↩︎

Benjamin, R. Race After Technology. Cambridge: Polity Press (2019). ↩︎

Johnson, J.M. “Markup Bodies: Black [Life] Studies and Slavery [Death] Studies at the Digital Crossroads.” Social Text, 36,4,137: pp. 57–79 (2018). ↩︎ ↩︎

D’Ignazio, C. and Klein, L. Data Feminism , Cambridge MA: MIT Press (2020). ↩︎

Noble S. U. “Algorithms of Oppression. How Search Engines Reinforce Racism” New York: NYU Press (2018). ↩︎

Weingart, S. B. and Eichmann-Kalwara, N. “What’s Under the Big Tent?: A Study of ADHO Conference Abstracts” Digital Studies/le Champ Numérique , 7 ,1, 6 (2017). ↩︎

Gallon, K. “Making a Case for the Black Digital Humanities” In M. Gold and L. Klein (Eds.), Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016 (pp. 42-49). Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press (2016). ↩︎

Noble, S. U. “Toward a Critical Black Digital Humanities” In M. Gold and L. Klein (Eds.), Debates in the Digital Humanities 2019 (pp. 27-35), Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press, http://doi:10.5749/j.ctvg251hk.5. ↩︎

Cong-Huyen, A., Lothian, A., & Philips, A. “Reflections on a Movement: #TransformDH, Growing Up” In M. Gold and L. Klein (Eds.), Debates in the Digital Humanities 2016 (pp. 71-80), Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press (2016). ↩︎

Risam, R. New Digital Worlds: Postcolonial Digital Humanities in Theory, Praxis, and Pedagogy , Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. ↩︎

Sneha, P.P. Mapping Digital Humanities in India, Banglore: The Center for Internet and Society. December 30 (2016). ↩︎

Posner, M. “Humanities Data: A Necessary Contradiction” June 25 (2015) http://miriamposner.com/blog/humanities-data-a-necessary-contradiction/. ↩︎

Bakhshi, S. I. “Digitization and Digital Preservation of Cultural Heritage in India with Special Reference to IGNCA, New Delhi” Asian Journal of Information Science and Technology, 6, 2, (2016). ↩︎

Zhizhong, L. Zhongguo guojia tushuguan guanshi . Beijing Shi: NLC Press (2009). ↩︎

Manaf, Z.A., “The state of digitization initiatives by cultural institutions in Malaysia: an exploratory survey” Library Review , 56, 1: pp. 45-60 (2007) ↩︎

Urgola, S. “Archiving Egypt’s revolution: ’the university on the square project’, documenting January 25, 2011 and beyond” IFLA Journal , 40, 1: pp. 12-16 (2014). ↩︎

Srinivasan, S., Diepeveen, S. and Karekwaivanane, G. “Rethinking publics in Africa in a digital age” Journal of Eastern African Studies , 13, 1 (2018). ↩︎

Kulesz, O. Culture in the digital environment: assessing impact in Latin America and Spain Paris: Unesco (2017). ↩︎

de Jong, A., and Wintermans, V. “Introduction” In Y. de Lusenet and V. Wintermans (eds.) Selected papers of the international conference organized by Netherlands National Commission for UNESCO, November 4, 2005, The Hague, The Netherlands, (2007). ↩︎

Moseley, R., and Wheatley, H. “Is Archiving a Feminist Issue? Historical Research and the Past, Present, and Future of Television Studies” Cinema Journal, 47 , 3): pp. 152-158 (2008). ↩︎

Collins, J. “Doing-it-together: Public history-making and activist archiving in online popular music community archives” In S. Baker (ed.) Preserving Popular Music Heritage: Do-it-Yourself, Do-it-Together (pp. 77-90). Abington: Taylor and Francis (2015). ↩︎

Zaagsma, G. “Digital History and the Politics of Digitization” Utrecht: ADHO DH conference Utrecht (2019). ↩︎

Spiro, L. “‘This Is Why We Fight’: Defining the Values of the Digital Humanities” In M. K. Gold (Ed.), Debates in Digital Humanities (online). Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press (2012), http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/13. ↩︎

Griffin, G. and Hayler, M. S. “Collaboration in Digital Humanities Research - Persisting Silences” Digital Humanities Quarterly , 12, 1: pp. 1-33. ↩︎

Fitzpatrick, K. Generous Thinking: A Radical Approach to Saving the University , Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press (2019). ↩︎