Digital Humanities & Film Studies: Analyzing the Modalities of Moving Images

Automated Visual Content Analysis for Film Studies: Current Status and Challenges

1 Introduction

In contrast to the field of computer-assisted research in the arts that has been established for several years 1 2 3 4, there is a need to catch up in scientific approaches to film (represented in the fields of New Film History and Stylometry). An important reason is the lack of practical software solutions available to date and the incompatibility of quantitative research designs with existing methodologies for film studies. In this context, some researchers criticise above all the appropriation of a technicistic, unrelated mission statement, which advocates of digital humanities apply to their own subject following other principles 5 6. However, more recent research 7 8 has shown that qualitative and quantitative analysis are by no means mutually exclusive, but can be integrated in order to enrich film studies with new impulses.

The statistical film analysis developed by the physicist Salt thus holds the potential of a methodological guideline for quantifying filmic characteristics 9 10. This methodology focuses on quantifiable factors in the formal structure of a film such as camera shot length, which is considered an objective unit because it can be measured over time. The various forms of camera usage and movement (such as tracking shots, pans and tilts, camera distance, i.e., shot size) as well as other techniques (such as zoom-in and -out or the use of a camera crane) are also relevant for quantification. Casting this set of techniques as measuring instruments, it is possible to obtain data that scientists can relate to verifiable criteria in terms of film production history and to formulate hypotheses that allow conclusions to be drawn about the formal stylistic development of the selected films. To this end, Salt’s concept allows for complete traceability of the measurement results and thus also of the numerical values to a theory set.

The concept was criticized for its reductionism 11, which prevents it from being connected to the qualitative research methods that dominate film studies. However, research in digital humanities has shown that quantitative parameters such as shot length are a suitable foundation for various analytical tools when it comes to the qualitative investigation of data (Tsivian 2008; Buckland 2009; many others). In this way, quantitative research according to Salt makes it possible to validate stylistic changes in the work of emigrated European directors due to technical opportunities of the American studio system, or even to collect the average shot lengths of numerous productions from the beginning of film history to the present. Such research allows researchers to draw conclusions about the progressive acceleration of editing and thus provides information about the development of film technology and changes in our viewing habits. These questions concerning stylistic research in film studies cannot be examined without a corresponding quantitative research design, although Salt’s concept remains too inflexible for broader application.

In this context, Korte’s work (2010) is regarded as pioneering (especially in German-speaking countries) in transferring quantitative methods into the framework of a qualitative analysis immanent in the work. An example for this is Rodenberg’s analysis of Zabriskie Point (directed by Michelangelo Antonioni, 1970) in Korte’s introduction to systematic film analysis (2010), which graphically depicts the stylistic structure of the film in an innovative way. Thus, for a detailed analysis Rodenberg visualises the adaption and alignment of editing rhythms to the characterisations of the persons in the narrative, and makes the alignment of music and narration comprehensible using diagrams. Heftberger (2016), for example, combines the analysis of historical sources such as editing diagrams and tables by the Russian director Vertov with computer-aided representations of digital humanities in order to provide insights into the filmmaker’s working methods. Heftberger starts with copies of Vertov’s films, which were analysed for structural features using the annotation software ANVIL 12, but also for dissolves or condition-related factors (e.g. markings in the film rolls or damage to the film). Within the framework of single and overall analyses, the data serve to elucidate the director’s intentions.

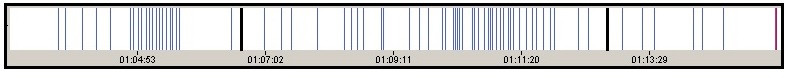

Increase and decrease of shot lengths in Antonioni’s Blow Up (1966) using Videana.

Sittel (2016) investigated the principle of increase and decrease of shot lengths in Michelangelo Antonioni’s Blow Up (1966). The visualization in Figure 1 was created during this study with the video analysis software Videana 13 and gives an insight into this pattern. This technique, which is increasingly used in film editing, represents a structuring feature of the second half of the film and can be interpreted as a message with regard to the film content.

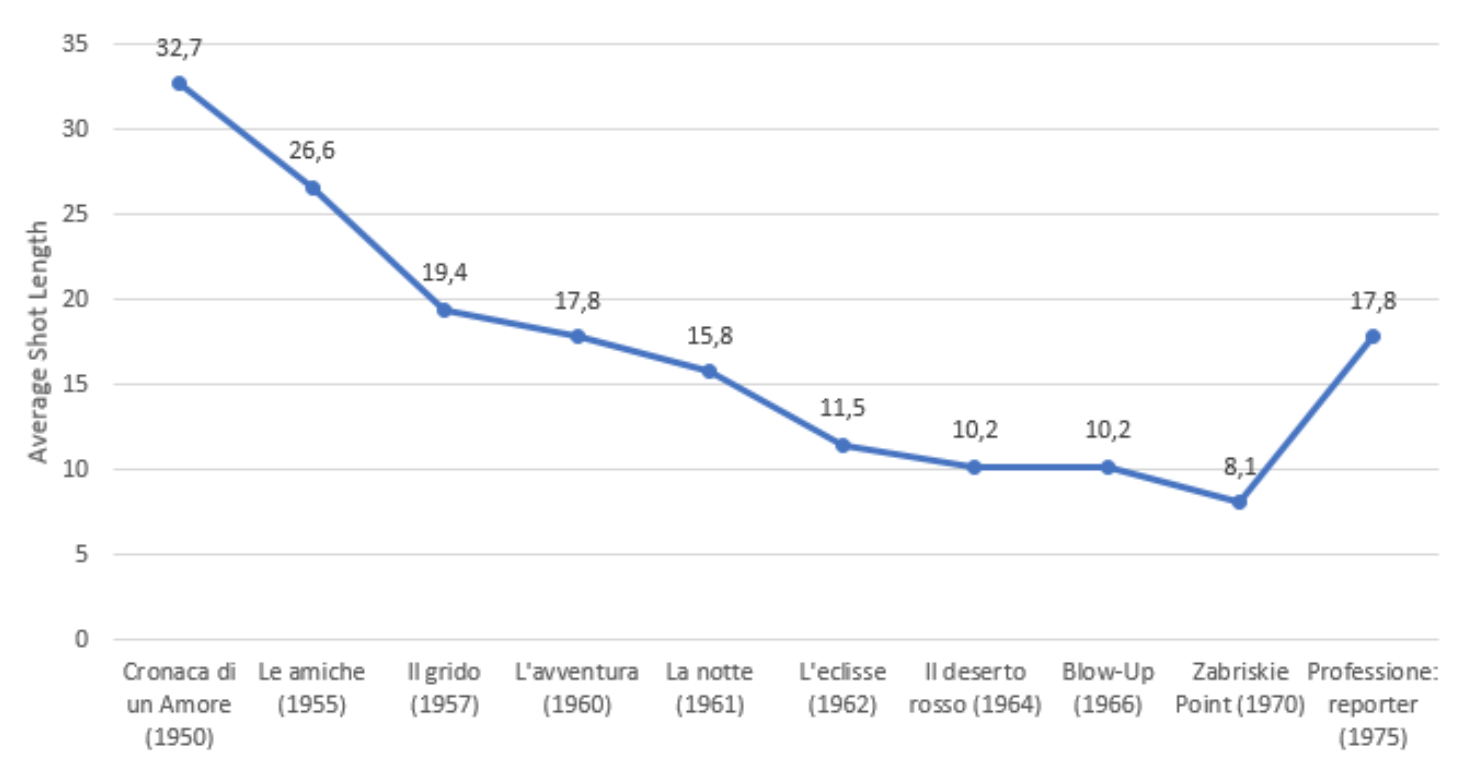

Average shot length of all Antonioni films in chronological order.

Using Salt’s paradigm as a guideline, an analysis of all Antonioni films makes it possible to identify a clear change in style based on shot sizes and camera movements, which extends existing, non-qualitative approaches in a differentiated way. Figure 2 shows that the average shot length becomes shorter across nearly all films. To this end, a principle of systematic camera movement (longer shots) and thus an abandonment of montage gradually gives way to the increasing use of editing.

Research efforts like this benefit from automated computer-based methods that measure basic features of filmic structure. Similar to former work 14, we present a comprehensive survey of related software tools for video annotation, but particularly focus on methods for visual content analysis for film studies. First, we examine major software tools for video analysis with a focus on automated analysis algorithms and discuss their advantages and drawbacks. In addition, related work that applies automated video analysis to film studies is discussed. Moreover, we summarise current progress in computer vision and visual content analysis with a focus on deep learning methods. Besides, a comparison of machine vs. human performance in annotation tasks that are relevant for video content analysis is provided. Finally, we discuss future desirable functionalities for automated analysis in software tools for film studies.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews existing software tools and algorithms for quantitative approaches in film analysis. Section 3 discusses recent advancements in the field of video analysis and computer vision. A comparison of human and machine performance in different annotation tasks is provided in Section 4. Section 5 describes requirements for software tools in scholarly film studies and outlines areas for future work.

2 Software Tools and Algorithms for Quantitative Film Studies

Researchers who want to utilise quantitative strategies to analyse film as presented in Figure 1 and 2 usually have to evaluate larger films or video corpora. However, existing software tools so far, with a few exceptions, require a high degree of manual annotation. As a consequence, many current film productions are difficult to evaluate due to ever shorter shot lengths. This section provides an overview of software solutions for film studies and their degree of automation in terms of capturing basic filmic features. While there are numerous existing annotation and video analysis tools, the focus lies on ready-to-use software applications most suitable for quantitative film studies. An overview of the functionalities provided by the selected applications and their current status of availability is presented in Table 1. We also distinguish between application areas in Table 1, since not all of the tools were originally proposed for scholarly film studies as targeted here.

Table 1. Overview of software applications for quantitative approaches in film analysis, characterised by their degree of automation regarding video content analysis tasks. While m denotes manual annotation, a refers to automated annotation.

Tool Application Area Availability Shot change detection Camera motion Video OCR Face detection Colour analysis Annotation level Visualisations Advene

Film studies/

teaching platform

Desktop App

(free)

a ROI

Timelines for shots &

annotation

ANVIL

Psycholinguistics/

social sciences

Desktop App

(free)

m Shot

Timelines for annotation tiers &

speech track

Cinemetrics

Film studies

Web-based crowd-sourcing platform m Shot Cut frequency diagram ELAN

Psycholinguistics/

social sciences

Desktop App

(free)

m Shot

Timelines for annotation tiers &

speech track segments

Ligne de Temps Film studies

Desktop App

(free)

a m Shot Timeline for cuts Media-thread Teaching platform

Web App

(source code available)

ROI Hyper video annotations VIAN

Film studies

(colour analysis)

Desktop App15

(not publicly available yet)

a a¹ a ROI Timelines for shots & annotations, colour schemes view, screenshot manager Videana

Media/

film studies

Desktop App

(on request until 2012)

a a a a a ROI

Timelines of detections annotations & cuts,

cut frequency diagram, shot list

2.1 Cinemetrics

In the Cinemetrics project 16, Yuri and Gunnar Tsivian took up Salt’s methodology and used it for the first time as conceptual guidelines for the implementation of digital analytical instruments, which are freely available as a Web-based platform since 2005.17 The tool allows the user to synchronously view and annotate video material, or to systematically comb through AVI video files. In the advanced mode, customized annotation criteria can be defined in addition to basic features (e.g. frequency and length of shots). The data sets obtained are then collected within an online database according to the principle of crowdsourcing. With metadata for more than 50,000 films to date, it acts as a comprehensive research data archive that documents the development and history of film style. Cinemetrics is the only platform based on Web 2.0 principles that consistently aggregates film data and makes it publicly accessible. However, the analysis of film data is not systematic. Moreover, Cinemetrics relies exclusively on the manual acquisition of data such as shot changes, camera distances, or camera movements. The accurate evaluation of video material such as feature films therefore requires an effort of several hours and is unsuitable for broader studies. Nonetheless, the platform enjoys a high level of visitor traffic. Between 2010 and 2013, the number of users almost doubled (2010: 4,500 clicks per day, 2013: 8,326). The program is regularly used in seminars at the Universities of Chicago, Amsterdam, Taiwan and at the Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz.

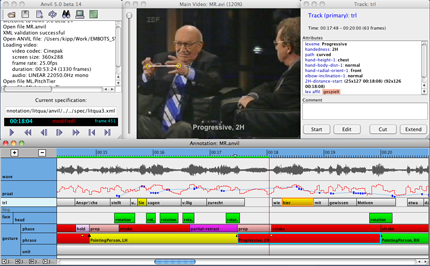

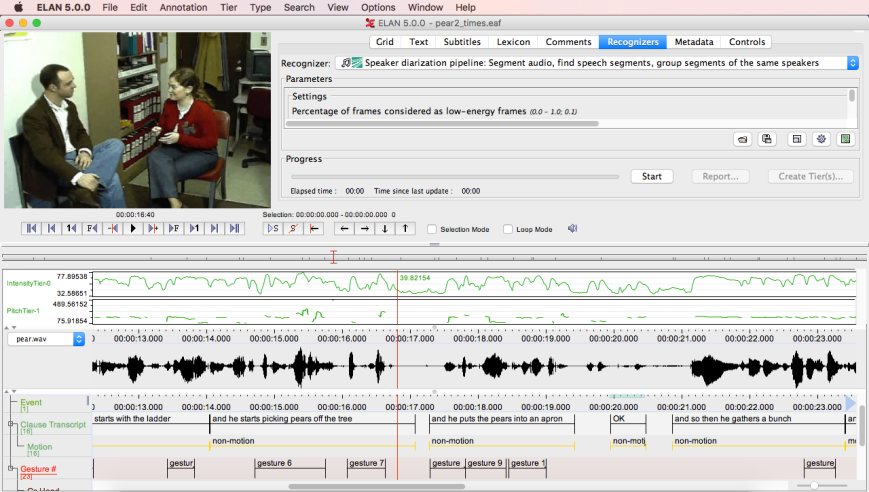

2.2 ANVIL, ELAN

ANVIL 18 12 and ELAN (EUDICO Linguistic Annotator)19 20 are visual annotation tools, which were originally designed for psycholinguistics and gesture research. They are suitable for the differentiated graphical representation of editing rhythms or for the annotation of previously defined structural features at the shot and sequence level, though it usually requires the export of the data to another statistical software or Microsoft Excel. In contrast to Cinemetrics, ANVIL and ELAN allow the user to directly interact with the video material. They offer a much greater methodological scope, especially through the option of adding several feature dimensions to the video material in the form of tracks. Both systems work according to a similar principle, to which the video segments or the collected shots can be viewed and annotated with metadata. Annotations can also be arranged hierarchically by means of multiple layers which are called tiers. Thus, annotations can be cross-referenced to other annotations or to corresponding shots or video segments, making the programs particularly suitable for a fine-grained analysis of the structure of individual works. However, if several parameters are to be recorded during an evaluation run, repeated viewing of a film is required in order to label the individual tracks with the respective characteristics and features.

Screenshot of ANVIL software.

Screenshot of ELAN software.

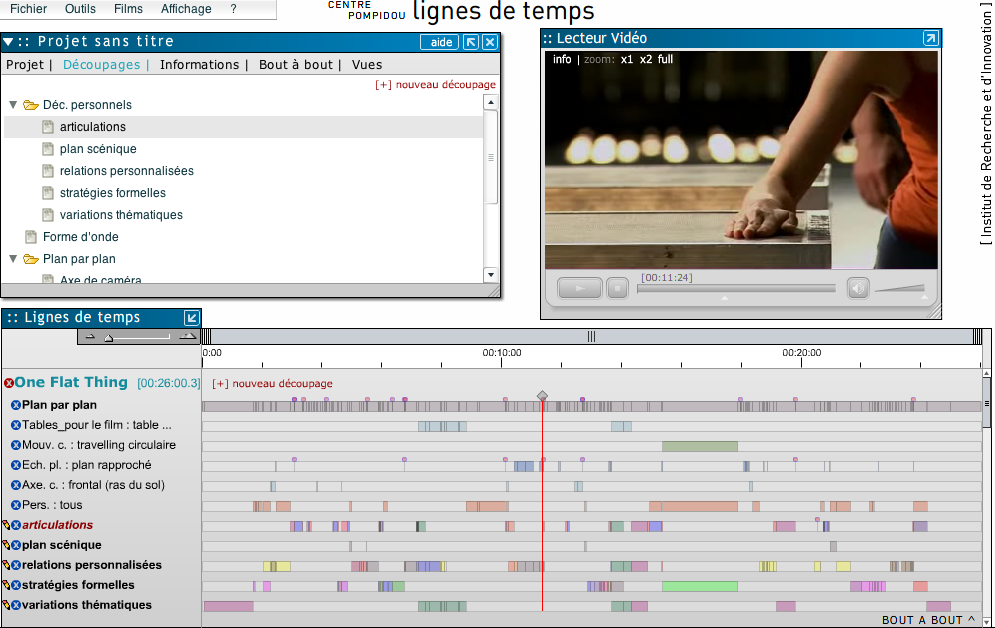

2.3 Ligne de temps

The analysis tool Ligne de temps21 was developed between 2007 and 2011 by the Institut de recherche et d’innovation du Centre Pompidou. The tool provides a graphical timeline-based representation of the material and allows for selecting temporal segments in order to annotate different types of modality (video, audio, text) of the corresponding sequence in the movie, or add information in the form of images or external links. Moreover, it is possible to generate colour-coded annotations aligned with the shots by choosing from a range of available RGB colour values. This function can be implicitly used for colour analysis. However, a single colour cannot represent a holistic image or even an entire shot. Ligne de temps enables the automated detection of shot boundaries in the video, as only few of the presented tools do. But there is no information available about the algorithm used and its performance on benchmark data sets.

Screenshot of Ligne de Temps.

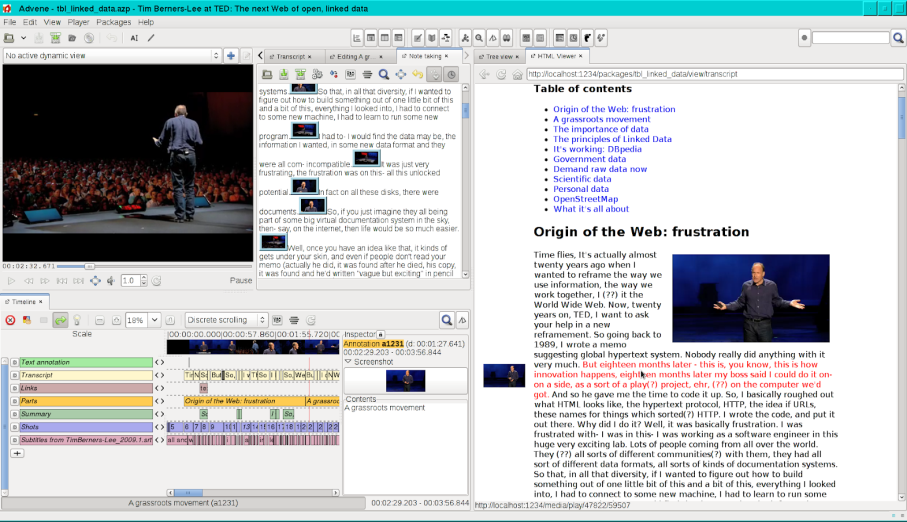

2.4 Advene, Mediathread

Advene (Annotate Digital Video, Exchange on the NEt) 22 is an ongoing project for the annotation of digital videos that also provides a format to share annotations. The tool has been developed since 2002 and is freely available as a cross-platform desktop application.23 It provides a broader number of functionalities compared with the former tools. In particular, the tool enables textual as well as graphical annotations to augment the video and also provides automatically generated thumbnails for each shot. Moreover, it is possible to edit and visualise hypervideos consisting of both the annotations and the video. Target groups are film scholars, teachers and students who want to exchange multimedia comments and analyses about videos such as movies, conferences, or courses. The tool has also been used for reflexive interviews of museum visitors, or with regard to on-demand video providers and movie-related social networks. However, the automatic analysis options that Advene provides are restricted to shot boundary detection and temporal segmentation of audio tracks.

Mediathread24 was developed by Columbia University’s Center for Teaching and Learning (CTL)25 and first launched in 2010. It is a web application for multimedia annotations enabling collaboration on video and image analysis. Similar to Advene, Mediathread primarily serves as a platform for collaboratively working and sharing annotations for multimedia and is therefore actively used in classroom environments at various universities, also including courses on film studies. However, it does not provide automated analysis capabilities such as shot detection. In addition, film studies researches wanting to use the web application need a certain degree of expertise to individually deploy the openly available source code.

Screenshot of Advene.

2.5 Videana

The video analysis software Videana was developed at the University of Marburg 13. Videana is one of the few software tools to offer more than simple analysis functions such as the detection of shot changes 26 27. For example, the software integrates algorithms for text detection 28, video OCR 29, estimation of camera motion 30 and of object motion 31, and face detection 32. Further functionalities, which are however not part of the standard version, are the recognition of dominant colour values, person recognition and indexing 33, or the temporal segmentation of the soundtrack. The many available features and the possibility to combine them allow for the flexible formulation of complex research hypotheses and their empirical verification. For example, Videana was used for a media study to investigate user behaviour in Google Earth Tours 34 35. However, the software has not been updated since 2012 and therefore does not rely on current state-of-the-art methods in video analysis. Another drawback of the tool is the lack of enhanced visualizations that go beyond simple cut frequency diagrams and event timelines. Finally, the software is not usable through a Web browser, but only available as a desktop software.

Screenshot of the main window of Videana (provided in Ewerth et al. 2009).

2.6 VIAN

Within the project “Film Colors - Bridging the Gap Between Technology and Aesthetics” 36 at the University of Zurich, the tool VIAN 37 for video analysis and annotation is currently being developed with a focus on film colour patterns. In comparison to general-purpose annotation tools like ELAN, VIAN particularly addresses aesthetic analyses of full feature films. The tool is also planned to allow a variety of (semi)-automatic tools for the analysis and visualisation of film colours based on computer vision and deep learning methods such as figure-ground separation and extraction of the corresponding colour schemes. Although the tool is not released yet (announced to be open source), VIAN seems to be a very promising tool with regard to state-of-the-art visual content analysis methods.

Figure 8. Screenshot of VIAN temporal segmentation and screenshot manager.

2.7 Other Tools and Approaches

There are some other tools that offer video and film analysis and (to a lesser extent) provide functions similar to the previously introduced applications for automatic film analysis. The Semantic Annotation Tool (SAT) is launched in the context of the Media Ecology Project (MEP) (http://mediaecology.dartmouth.edu/sat/). It allows for the annotation and sharing of videos on the Web in free-text form, by a controlled set of tags, or polygonal regions in a frame. It targets classroom as well as research environments. The tool itself does not provide (integrated) quantitative measures. However, it can be fed with external machine-generated metadata (by automated video analysis methods). The Distant Viewing Toolkit38 is a python package that provides computational analysis and visualisation methods for video collections. The software extracts and visualises semantic metadata from videos using standard computer vision methods as well as exploring more high-level patterns such as screen time per character. Another project is eFilms39 that provides a web-based film player that is supplemented with contextual meta information such as date, geolocation or visual events for the footage. Its main use case is the contextualization of historical footage of the Nazi era. The project also provides a film annotation editor to insert the context annotations. However, as for the aforementioned projects as well, the source code needs to be deployed first and thus is no off-the-shelf and ready-to-use solution for film scholars. Furthermore, the SAT and eFilms tools only offer manual annotation.

Many other works exist that deal with analysis and visualisation of certain filmic aspects. Some early works by Adams et al. transfer concepts of film grammar to computational measures for automated film analysis. Adams and Dorai (2000) introduce a computational measure of movie tempo based on its filmic definition and use it to automatically extract dramatic sections and events from film. Furthermore, Adams et al. (2001) present a computational model for extracting film rhythm by deriving classes for different motion characteristics in order to identify narrative structures and dramatic progression. Another work deals with the extraction of narrative act boundaries, in particular the 3-act-story telling paradigm using a probabilistic model 40.

Pause and Walkowski (2016) address the characterization of dominant colours in film and discuss the limitations of the k-means clustering approach. Furthermore, they propose to proceed according to Itten’s method of seven colour contrasts (2016) and outline how it can be implemented algorithmically. Burghardt et al. (2016) present a system that automatically extracts colour and language information using k-means clustering as well as subtitles and propose an interactive visualisation. Hoyt et al. (2014) propose a tool to visualise the relationships between characters in a movie. John et al. (2017) present a visual analytics approach (for the analysis of single or a set of videos) that combines automatic data analysis and visualisation. The interface supports the representation of so-called semantic frames, simple keywords, hierarchical annotations, as well as keywords for categories and similarities. Hohman et al (2017) propose a method to explore individual videos (entertainment, series) on the basis of colour information (dominant colour, etc.) as well as texts from dialogues and evaluate the approach on the basis of two use cases for the series Game of Thrones .

Tseng (2013b) provides an analysis of plot cohesion in film by tracking film elements such as characters, objects, settings, and character action. Furthermore, Tseng (2013a) distinguishes basic narrative types in visual images by interconnecting salient people, objects and settings within single and across sequential images. Bateman (2014) reviews empirical, quantitative approaches to the analysis of films and, moreover, suggests employing discourse semantics for more systematic interpretative analysis in order to overcome the difficulty of relating particular technical film features to qualitative interpretations.

3 Current Developments in Computer Vision and Video Analysis

Apart from analysing film style (shot and scene segmentation, use of camera motion and colours, etc.), film studies are also concerned with question(s) such as: Who (or what) did what, when, and where?. To answer such questions, algorithms for recognising persons, location and time of shots, etc. are required. There are some state-of-the-art approaches that basically target these questions (e.g., visual concept detection, geolocation and date estimation of images) and might be applicable to film style and content analysis – at least in future work.

A central question in computer vision approaches is the choice of a feature representation for the visual data. Classical approaches rely on hand-crafted feature descriptors. While global descriptors like Histogram of Oriented Gradients (HOG) are considered to represent an image holistically, descriptors based on Scale Invariant Feature Transform (SIFT) 41 or Speeded Up Robust Features (SURF) 42 have proven to be particularly suitable for local features since they are invariant to coordinate transformations, and robust to noise as well as to illumination changes. With the emergence of deep learning, however, feature representations based on convolutional neural networks (CNNs) largely replaced hand-crafted low-level features. Nowadays, CNNs and deep features are the state-of-the-art for many computer vision tasks 43 44 45.

3.1 Shot Boundary Detection

Shot boundary detection (SBD) is an essential prerequisite for video processing and for video content analysis tasks. Typical techniques in SBD 46 47 48 rely on low-level features, consisting of global or local frame features that are used to measure the distance between consecutive frames. One notable approach 49 utilises both colour histograms and SURF descriptors 42 along with GPU acceleration to identify abrupt and gradual transitions in real time. This approach achieves a F1 accuracy score of 0.902 on a collection of 15 videos gathered from different video archives while being 3x faster than real-time processing on GPU. In order to enhance detection, especially for more subtle gradual transitions, several CNN-based proposals have been introduced. They extract and employ representative deep features for frames 50 or train networks that detect shot boundaries directly 51. Xu et al. conduct experiments on TRECVID 2001 test data and achieve F1 scores of 0.988 and 0.968 for cut and gradual transitions, respectively. Gygli (2018) reports a F1 score of 0.88 on the RAI dataset 52 outperforming previous work, while being extremely fast (more than 120x real-time on GPU).

3.2 Scene Detection

Given the shots, it is often desirable to segment a broadcast video into higher level scenes. A scene is considered as a sequence of shots, which are related in a spatio-temporal manner. For this purpose, Baraldi et al. (2015b) detect superordinate scenes describing shots by means of colour histograms and subsequently apply a hierarchical clustering approach. The approach is applied to a collection of ten randomly selected broadcasting videos from the RAI Scuola video archive constituting the RAI dataset. The method achieves a F1 score of 0.70 at 7.7x real-time on CPU. Sidiropoulos et al. (2011) suggest an alternative approach, where shots constitute nodes in a graph representation and edges between shots are weighted by shot similarity. Exploiting this representation, scenes can be determined by partitioning the graph. On a test set of six movies as well as on a set of 15 documentary films, the approach obtains a F1 accuracy of 0.869 and 0.890 (F1 score on RAI dataset of Baraldi et al. 2015b: 0.54), respectively. Another solution 53 is to apply a multimodal deep neural network to learn a metric for rating the difference between pairs of shots utilizing both visual and textual features from the transcript. Similarity scores of shots are used to segment the video into scenes. Beraldi et al. evaluate the approach on 11 episodes from the BBC educational TV series Planet Earth and report a F1 score of 0.62.

3.3 Camera Motion Estimation

Camera motion is considered as a significant element in film production. Thus, estimating the types of camera motion can be helpful in breaking down a video sequence into shots or for motion analysis of objects. Some techniques for camera motion estimation perform direct optical flow computation 54, while others consider motion vectors that are available in compressed video files 30. On four short movie sequences Nguyen et al. individually obtain 94.04% to 98.26% precision (percentage of correct detections). The latter approach is evaluated on a video test set consisting of 32 video sequences including all kinds of motion types. It detects zooming with 99%, tilting (vertical camera movement) with 93% and panning (horizontal camera movement) with 79% precision among other motion types. This approach achieved the best results in the task of zoom detection at TRECVID 2005. More recent works in this field couple the camera motion problem with similar tasks in order to train neural networks in a joint unsupervised framework 55 56 57.

3.4 Object Detection and Visual Concept Classification

Object detection is the task of localising and classifying objects in an image. Motivated by the first application of CNNs to object classification 58, regions with CNN features (R-CNN) were introduced in order to (localize and) classify objects based on region proposals 59. However, since this approach is computationally very expensive, several improvements have been proposed. Fast-R-CNNs 60 were designed to jointly train feature extraction, classification and bounding box regression in an unified network. Additionally integrating a region proposal subnetwork enabled Faster-R-CNNs 61 to significantly speed up the formerly separate process of generating regions of interest. Thus, Faster-R-CNNs achieve an accuracy of 42.7 mAP (mean Average Precision) at a frame rate of 5 fps (frames per second) on the challenging MS COCO detection dataset 62 (MSCOCO: Microsoft Common Objects in Context). Furthermore, mask R-CNNs 63extend the Faster-R-CNN approach for pixel-level segmentation of object instances by predicting object masks. Running at 5 fps, this approach predicts object boxes as well as segments with an accuracy of 60.3 mAP and 58.0 mAP on the COCO dataset. In contrast to region proposal based methods, Redmon et al. (2016) introduced YOLO, a single shot object detector that predicts bounding boxes and associated object classes based on a fixed-grid regression. While YOLO is very fast in terms of inference time, further extensions 64 65 employ anchor boxes and make several improvements on network design also boosting the overall detection accuracy to 57.9 mAP at 20 fps on the COCO dataset. In order to detect a wide variety of over 9000 object categories, Redmon and Farhadi (2017) also introduced the real-time system YOLO9000, which was simultaneously trained on the COCO detection dataset as well as the ImageNet classification dataset 66. Apart from detecting objects, there were also many approaches and more importantly datasets introduced for classifying images into concepts. The SUN database 67 provides up to 5400 categories of objects and scenes. Current image concept classification approaches typically rely on deep models trained with state-of-the-art architectures 68 69 70.

3.5 Face Recognition and Person Identification

Motivated by the significant progress in object classification, deep learning methods have also been applied to face recognition. In this context, DeepFace 71 is one of the first approaches that is trained to obtain deep features for face verification and, moreover, enhances face alignment based on explicit 3D modelling of faces. This approach achieves an accuracy of 97.35% on the prominent as well as challenging Labeled Faces in the Wild (LFW) benchmark set. While DeepFace uses a cross-entropy loss (cost function) for feature learning, Schroff et al. (2015) introduced with FaceNet a novel and more sophisticated loss based on training with triplets of roughly aligned matching and nonmatching face patches. On the LFW benchmark, FaceNet obtains an accuracy of 99.63%.

In the context of broadcast videos, the task of detecting faces and clustering them for person indexing of frames or shots has been widely studied (e.g., Ewerth et al. 2007b). While Müller et al. (2016) present a semi-supervised system for automatically naming characters in TV broadcasts by extending and correcting weakly labelled training data, Jin et al. (2017) both detect faces and cluster them by identity in full-length movies. For content-based video retrieval in broadcast videos face recognition as well as concept detection based on deep learning have also been proven to be effective 72.

3.6 Recognition of Places and Geolocation

Recognising a place in a frame or shot might yield also useful information for film studies. The Places database contains over 400 unique place categories for scene recognition. Along with the dataset, Zhou et al. (2014; 2018) provide CNN models trained with various architectures on the Places365 dataset. Using the ResNet architecture 68, for example, a top-5 accuracy of 85.1% can be obtained on the Places365 validation set. Mallya and Lazebnik (2018) introduce PackNet for training multiple tasks in a single model by pruning redundant parameters. Thus, the network is trained on classes of the ImageNet as well as the Places365 dataset. Being trained on multiple tasks, the model yields a top-5 classification error of 15.6% for the Places365 classes on the validation set, while the individually trained network by Zhou et al. (2018) shows a top-5 error rate of 16.1%. Hu et al. (2018) introduce a novel CNN architecture unit called SE block, which enables a network to use global information to selectively emphasise informative features and suppress less useful ones by performing dynamic channel-wise feature recalibration. This approach was trained on the Places365 dataset as well and shows a top-5 error rate of 11.0% on the corresponding validation set.

For the task of earth scale photo geolocation two major directions have been taken so far. Im2GPS, one fundamental proposal for photo geolocation estimation, infers GPS coordinates by matching the query image against a reference database of geotagged images 73 74 and was recently enhanced by incorporating deep learning features 75. In this context, the Im2GPS test set consisting of 237 challenging photos (only 5% are depicting touristic sites) was introduced. The latest deep feature based Im2GPS version 75 achieves an accuracy of 47.7% at region scale (location error less than 200 km). Other major proposals cast the task as a CNN-based classification approach by partitioning the earth into geographical cells 76 and considering combinatorial partitioning of maps, which facilitate more accurate and robust class predictions 77. These frameworks called PlaNet and CPlaNet achieve 37.6% and 42.6% accuracy at region scale on the benchmark, respectively. Current state-of-the-art results (51.9% accuracy at region scale) are achieved by similarly combining hierarchical map partitions and additionally distinguishing three different settings (indoor, urban, and rural) through automatic scene recognition 78.

3.7 Image Date Estimation

While unrestricted photo geolocation estimation is well covered by several studies, the problem of estimating the date of arbitrary (historical) photos was addressed less frequently in the past. The first unrestricted work in this context 79 dates historical colour images from 1930 to 1980 utilizing colour descriptors that model the evolution of colour imaging processes over time. Thus, Palermo et al. report an overall accuracy of 45.7% on a set of 1375 Flickr images which are uniformly distributed across the considered decades. A recent deep learning approach 80 dates images from 1930 to 1999 considering the task either as a classification or a regression problem. Müller et al. introduce the Date Estimation in the Wild test set consisting of 1120 Flickr images, which cover every year uniformly, and report a mean estimation error of less than 8 years for both the classification and regression models.

4 Human and Machine Performance in Annotation Tasks

When applying computer vision approaches to film studies, the question arises whether their accuracy is sufficiently high. In this respect, we provide a comparison of human and machine performance based on own previous work 81 for some specific visual recognition tasks: face recognition, geolocation estimation of photos, date estimation of photos, as well as visual object and concept detection (Table 2).

A major field where human and machine performance has been compared frequently is visual concept classification. For a long time human annotations were (significantly) superior to machine-generated ones, as demonstrated by many studies 82 83 84 on datasets like PASCAL VOC or SUN. However, the accuracy of machine annotations could be significantly raised by deep convolutional neural networks. The error rate of 6.7% reported with GoogLeNet 85 on the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge (ILSVRC) 2014 was already close to that of humans (5.1 %), until in 2015 the error rate of neural networks 86 was slightly lower (error rate: 4.94%) than human error on the ImageNet challenge. However, the human error rate is only based on a single annotator. Hence, no information about human inter-annotator agreement is available.

Comparison of human and machine performance in visual recognition tasks. Approach Challenge/test set Error Metric Human Performance Machine Performance Visual Concept Classification

GoogLeNet

85

ILSVRC’14 Top-5 test error 5.1% 6.66% He et al. 2015 ImageNet’12 dataset Top-5 test error 5.1% 4.94% Face Verification

DeepFace

71

LFW Accuracy 97.53% 97.35%

FaceNet

87

LFW Accuracy 97.53% 99.63% Geolocation Estimation

PlaNet

76

Im2GPS test set

Accuracy at

region/continent scale

3.8% / 39.3% 37.6% / 71.3%

Im2GPS

75

Im2GPS test set

Accuracy at

region/continent scale

3.8% / 39.3% 47.7% / 73.4%

CPlaNet

77

Im2GPS test set

Accuracy at

region/continent scale

3.8% / 39.3% 46.4% / 78.5% 78 Im2GPS test set

Accuracy at

region/continent scale

3.8% / 39.3% 51.9% / 80.2% Date Estimation 79 Test set crawled from Flickr

Classification accuracy

by decade

26.0% 45.7% 80 _Date Estimation in the Wild _ test set

Absolute mean error

(in years)

10.9% 7.3%

A comparison of face identification capabilities of humans and machines was made for the first time in a Face Recognition Vendor Test (FRVT) study in 2006 88. Thus, it has been shown - interestingly, already nearly 15 years ago - that industry-strength methods can compete with human performance in identifying unfamiliar faces under illumination changes. On the more recent as well as more challenging Labeled Faces in the Wild (LFW) benchmark, human performance has also been reached by several approaches. Among several others, DeepFace 71 and FaceNet 87 are prominent deep learning approaches reporting human-level (97.53%) results of 97.35% and 99.63% accuracy on the benchmark, practically solving the LFW dataset.

While humans are relatively good at recognising persons, estimating or guessing the location and date of an image imposes a more difficult task for subtle spatial as well as temporal differences. Various systems have been proposed for earth scale photo geolocation that outperform human performance in this task. The latest of these 77 75 76 employ deep learning methods consuming up to 90 million training images for an imposed classification task of cellular earth regions and/or rely on an extensive retrieval database. Current state-of-the-art results are reached by considering hierarchical as well as scene information of photos within the established classification approach, while using only 5 million training images 78. Since human performance reported on the established Im2GPS benchmark 75 is relatively poor in this task, the system clearly surpasses human ability to guess geolocation by 48.1% accuracy within a tolerated distance level of 200 km (predictions at region level).

The creation date of (historical) photos is very hard to judge for periods of time that are quite similar. Therefore, a fundamental work 79 predicts the decade of historical colour photos with an accuracy of 45.7% exceeding that of untrained humans (26.0% accuracy), Müller et al. (2017) suggest a deep learning system that infers the capturing date of images taken between 1930 and 1999 in terms of 5-year periods. When comparing human and machine annotations by means of absolute mean error in years, the deep learning system achieves better results nearly at all periods and improves the overall mean error by more than three years.

In general, the promising performance of the computer vision approaches compared to humans in Table 2 makes a strong case for their use in film studies. Although these methods are still prone to errors (to a lesser or greater extent), they can highly raise the exploration of media sources and help in finding patterns. In spite of the impressive performance of the selected approaches, computer vision approaches still have some shortcomings. Such approaches are optimized for specific visual content analysis tasks and rely on custom training data. Therefore, they have limited flexibility and cannot adapt to arbitrary images across different genres. While they perform well in basic computer vision tasks, humans are by far superior in grasping and interpreting images in their context, for example, in identifying gradual transitions between shots or in captioning images/videos.

5 Conclusions and Future Prospects for Software Tools in Film Studies

In this paper, we have reviewed off-the-shelf software solutions for film studies. Since quantitative approaches to film content analysis are a handy way to effectively explore basic filmic features (see Section 1), we have put a focus on offered functionalities regarding automated film style and content analysis. In this respect, only the tools Videana and VIAN offer a wider range of automated video analysis methods. However, with Videana not being developed anymore and the most recent tool VIAN focusing on film colour patterns, the field still lacks available tools that provide powerful state-of-the-art methods for visual content analysis. We discuss needed functionality in detail in the latter part of this section. Furthermore, we have outlined recent advances in the (automated) analysis of film style (shot and scene segmentation, use of camera motion or colours) as well as current developments and progress in the field of computer vision. As also discussed in the beginning of this paper, quantitative approaches are partially criticised for being incompatible with qualitative film analysis. To showcase the chances of basic computer vision approaches, we have compared machine and human performance in visual annotation tasks. We have shown that machine annotations are of similar quality to those of humans for some basic tasks like object classification, face recognition or geolocation estimation. Even when these methods do not reach human abilities, they can build a valid basis for exploring media sources for further manual inspection.

What kind of basic and extended functionality for automated analysis and visualisation should a software tool have in order to support research in film studies? Previous practical experience with the basic functions of Videana has shown that such software is basically suitable for effectively supporting film research and teaching. However, film scholars often need more advanced functions tailored to their particular domain that allow the automatic detection of complex stylistic film elements such as the shot-reverse-shot technique. This requires, for example, detecting a series of alternating close-ups with a dialogue component and can be detected through the syntactic interaction of different factors. Starting from the smallest discontinuity in film, the cut, it is also possible to detect changing colour values or certain structural semantic properties such as the position of an object within consecutive shots. These could also allow drawing conclusions about changes within the storyline. Such forms of automatic segmentation and creating individual segments of events can be relevant in the context of narrative analyses. Researchers could be offered an effective structuring and orientation aid, which can undergo further manual differentiation based on content-related or motivic aspects. Therefore we envision a program that also offers a high degree of flexibility with regard to manual annotation opportunities. For a specific film or film corpus, individual survey parameters must be generated in order to judge their correlation with other parameters - depending on which hypotheses are to be applied to the object of investigation or can be formulated on the basis of the film material.

Considering, for example, a film as a system of information mediation as in quantitative suspense research 89 90 91, individual shots and sequences could be detected using automatic methods and manually be supplemented with further content parameters. Here, classifications such as the degree of information shared between the film character and the viewer (if the film viewer knows more or less than the character), the degree of correspondence between narrative time (duration of the film) and narrated time (time period covered by the filmic narrative), or the degree of narrative relevance (is the event only of relevance within the sequence or does it affect the central conflict of the narrative) are considered in order to draw conclusions about the suspense potential of a sequence. In the outlined framework, these factors favour the exploitation of the viewer’s anticipation of damage - in particular their emotional connection to a film character - through a principle of delay, as primarily applied in battle sequences typical of action films. Due to the principle of delaying the resolution of a conflict, they have a low information gain in view of the entire narrative. The principles of this parameterisation can now be used to check which dramaturgical context is characterised by which formal characteristics in comparison with the editing parameters of Salt. This concept of data acquisition can be extended by further parameters such as the application of digital visual effects in individual sequences, which provides a differentiated insight into the internal dynamics and proportions of filmic representation systems. Especially with regard to computer-generated imagery, which is subject to development processes spanning decades, it is possible to examine on a longitudinal scale how this process has had a concrete effect on production practices. However, such highly complex interwoven data structures require sophisticated statistical models with which these hypotheses can be tested.

Finally, a software tool adapted to the research object should be developed in a productive dialogue between computer science and film science. Such software for film studies could be based on experiences with software such as Videana or VIAN that allows for the evaluation of larger film corpora on a differentiated and reliable data basis, which cannot be generated with previous analysis instruments. Furthermore, it is desirable to include specific forms of information visualisations tailored to the needs of film scholars. Cinemetrics or Ligne de temps, as software designed for film studies, are also limited to a graphical representation that cannot take into account the requirements of narrative questions. Since an all-in-one approach will not fit to all analysis and visualisation requirements, such a tool should also provide an interface for plugins that offer additional functionality. Using these approaches, a large collection of research data can be gathered and exported for further processing, but the lack of a working digital environment for media science continues to be a problem. Statistical software or Microsoft Excel were not designed for the visualization of editing rhythms or narrative structures, which makes it difficult to process the corresponding data. An interdisciplinary cooperation could foster research in designing an optimal solution for scholarly film studies that allows direct interaction with the automatically determined parameters as well as their method-dependent annotation and graphical processing.

In summary, the development of a comprehensive software solution for scientists who systematically carry out film or video analysis would be desirable. This group includes media and film scientists, but also scientists from other disciplines (e.g., applications in journalism and media education, analysis of propaganda videos and political video works, image and educational films, television programmes). Also, empirical studies of media psychology in the field of event indexing require the annotation and analysis of structural properties of audiovisual research data. Factors such as the duration of an action segment as well as temporal, spatial, figure-related or action-related changes within the sequences (four dimension models), but also shot lengths are integrated into the research design and are prerequisites for the formulation of hypotheses and their empirical validation 92.

An interdisciplinary all-in-one software tool of this kind should be openly available on a web-based platform, intuitive, easy to use and rely on state-of-the-art algorithms and technology. On the one hand, by providing automatic methods for the quantitative analysis of film material, large film and video corpora could become the object of investigation and hypotheses could, for example, be statistically tested; on the other hand, the interpretation would be simplified by different possibilities of visualisation. Last but not least, legal questions regarding the storage, processing and use of moving image material should be clarified and taken into account in the technical implementation.

Anitha A., Brasoveanu, A., Duarte M., Hughes, S., Daubechies, I., Dik, J., Janssens, K., & Alfeld, M. “Restoration of X-ray fluorescence images of hidden paintings.” Signal Processing , 93(3) (2013): 592-604. ↩︎

Johnson, C. R., Hendriks, E., Berezhnoy, I. J., Brevdo, E., Hughes, S. M., Daubechies, I., & Wang, J. Z. “Image processing for artist identification.” IEEE Signal Processing Magazine , 25(4) (2008): 37-48. ↩︎

Klein C., Betz J., Hirschbuehl M., Fuchs C., Schmiedtová B., Engelbrecht M., Mueller-Paul, J., & Rosenberg, R. “Describing Art – An Interdisciplinary Approach to the Effects of Speaking on Gaze Movements during the Beholding of Paintings.” PLoS ONE 9(12) (2014). ↩︎

Resig, J. “Using computer vision to increase the research potential of photo archives.” Journal of Digital Humanities , 3(2) (2014): 33. ↩︎

Liu, A. “Where Is Cultural Criticism in the Digital Humanities?” [Online] (2012). Available at: http://dhdebates.gc.cuny.edu/debates/text/20 (Accessed: 19 December 2018) ↩︎

Missomelius, P. “Medienbildung und Digital Humanities: Die Medienvergessenheit technisierter Geisteswissenschaften.” In: Ortner, H., Pfurtscheller, D., Rizzolli, M, & Wiesinger, A. (Hg.): Datenflut und Informationskanäle . Innsbruck: Innsbruck UP (2014), 101-112. ↩︎

Heftberger, A. Kollision der Kader: Dziga Vertovs Filme, die Visualisierung ihrer Strukturen und die Digital Humanities , München: edition text+kritik (2016). ↩︎

Sittel, J. “Digital Humanities in der Filmwissenschaft.” In: ZfM 4 (2017), 472-489. ↩︎

Salt, B . Moving into Pictures . London: Starword (2006). ↩︎

Salt, B. Film Style and Technology: History and Analysis . London: Starword (2009). ↩︎

Flückiger, B. “Die Vermessung ästhetischer Erscheinungen.” ZfM 5 (2011): 44-60. ↩︎

Kipp, M. (2001). “Anvil - A Generic Annotation Tool for Multimodal Dialogue.” In: Proceedings of the 7th European Conference on Speech Communication and Technology (Eurospeech) (2001), pp. 1367-1370. ↩︎ ↩︎

Ewerth, R., Mühling, M., Stadelmann, T., Gllavata, J., Grauer, M., & Freisleben, B. “Videana: A Software Toolkit for Scientific Film Studies.” Digital Tools in Media Studies – Analysis and Research. An Overview. Transcript Verlag, Bielefeld, Germany (2009): 101-116. ↩︎ ↩︎

Estrada, L. M, Hielscher, E. Koolen, M., Olesen, C. G., Noordegraaf, J. & Jaap Blom, J. “Film Analysis as Annotation: Exploring Current Tools.” The Moving Image - Special Issue on Digital Humanities and/in Film Archives (Vol 17, no 2) (2017): 40-70. ↩︎

background-character/figure segmentation ↩︎

Tsivian, Y. “Cinemetrics, Part of the Humanities’ Cyberinfrastructure.” In: Michael Ross, Manfred Grauer, Bernd Freisleben (eds.), Digital Tools in Media Studies 9, Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag (2009): 93-100. ↩︎

Available at http://www.anvil-software.org/ ↩︎

Available at https://tla.mpi.nl/tools/tla-tools/elan/ ↩︎

Sloetjes, H., & Wittenburg, P. “Annotation by category – ELAN and ISO DCR.” In: Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation (2008). ↩︎

http://www.iri.centrepompidou.fr/outils/lignes-de-temps-2/ ↩︎

Aubert, O. & Prié, Y. “Advene: Active reading through hypervideo.” In: Proceedings of ACM Hypertext ‘05 (2005), pp. 235-244. ↩︎

Ewerth, R. & Freisleben, B. “Video Cut Detection without Thresholds.” In: Proc. of 11th Workshop on Signals, Systems and Image Processing , Poznan, Poland (2004), pp. 227-230. ↩︎

Ewerth, R. & Freisleben, B. “Unsupervised Detection of Gradual Shot Changes with Motion-Based False Alarm Removal.” In: Proceedings of 8th International Conference on Advanced Concepts for Intelligent Vision Systems (ACIVS) , Bordeaux, France, Springer (2009), pp. 253-264. ↩︎

Gllavata, J., Ewerth, R., & Freisleben, B. “Text Detection in Images Based on Unsupervised Classification of High-Frequency Wavelet Coefficients.” ICPR (2004), pp. 425-428. ↩︎

Gllavata, J., Ewerth, R., & Freisleben, B. “Tracking text in MPEG videos.” In: ACM Multimedia (2004), pp. 240-243. ↩︎

Ewerth, R., Schwalb, M., Tessmann, P., & Freisleben, B. “Estimation of Arbitrary Camera Motion in MPEG Videos.” In: Proceedings of 17th Int. Conference on Pattern Recognition , (2004), pp. 512–515. ↩︎ ↩︎

Ewerth, R., Schwalb, M., Tessmann, P., & Freisleben, B. “Segmenting Moving Objects in the Presence of Camera Motion.” In: Proc. of 14th Int. Conference on Image Analysis and Processing , Modena, Italy (2007), pp. 819-824. ↩︎

Viola, P. & Jones, M. “Robust Real-Time Face Detection.” Int. Journal of Computer Vision , 57(2) (2004): 137–154. ↩︎

Ewerth, R., Mühling, M., & Freisleben, B. “Self-Supervised Learning of Face Appearances in TV Casts and Movies.” Invited Paper (Best papers from IEEE International Symposium on Multimedia ‘06): International Journal on Semantic Computing, World Scientific (2007), pp. 185-204. ↩︎

Abend, P., Thielmann, T., Ewerth, R., Seiler, D., Mühling, M., Döring, J., Grauer, M., & Freisleben, B. “Geobrowsing the Globe: A Geovisual Analysis of Google Earth Usage.” In: Proc. of Linking GeoVisualization with Spatial Analysis and Modeling (GeoViz), Hamburg, (2011). ↩︎

Abend, P., Thielmann, T., Ewerth, R., Seiler, D., Mühling, M., Döring, J., Grauer, M., & Freisleben, B. “Geobrowsing Behaviour in Google Earth: A Semantic Video Content Analysis of On-Screen Navigation.” In: Proc. of Geoinformatics Forum , Salzburg, Österreich, (2012), pp. 2-13. ↩︎

Flückiger, B., Evirgen, N., Paredes, E. G., Ballester-Ripoll, R., & Pajarola, R. “Deep Learning Tools for Foreground-Aware Analysis of Film Colors.” In: Computer Vision in Digital Humanities , Digital Humanities Conference, Montreal (2017). ↩︎

Adams, B., Venkatesh, S., Bui, H. H. & Dorai, C. “A Probabilistic Framework for Extracting Narrative Act Boundaries and Semantics in Motion Pictures.” Multimedia Tools Appl. 27(2) (2005): 195-213. ↩︎

Lowe, D. G. “Distinctive Image Features from Scale-Invariant Keypoints.” International Journal of Computer Vision , 60(2) (2004): 91–110. ↩︎

Bay, H., Ess, A., Tuytelaars, T., & Van Gool, L. “Speeded-Up Robust Features (SURF).” Computer Vision and Image Understanding , 110(3) (2008): 346-359. ↩︎ ↩︎

Brejcha, J. & Cadík, M. “State-of-the-art in visual geo-localization.” Pattern Analysis and Applications , 20(3) (2017): 613-637. ↩︎

Rawat, W. & Wang, Z. “Deep Convolutional Neural Networks for Image Classification: A Comprehensive Review.” Neural Computation 29(9) (2017): 2352-2449. ↩︎

Wang, M. & Deng, W. “Deep Face Recognition: A Survey.” CoRR abs/1804.06655 (2018). ↩︎

Baber, J., Afzulpurkar, N. V., Dailey, M. N., & Bakhtyar, M. “Shot boundary detection from videos using entropy and local descriptor.” In: Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Digital Signal Processing , Corfu, Greece (2011), pp. 1-6. ↩︎

Lankinen, J., & Kämäräinen, J. “Video Shot Boundary Detection Using Visual Bag-of-Words.” In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications (1), Barcelona, Spain (2013), pp. 788-791. ↩︎

Li, J., Ding, Y., Shi, Y., & Li, W. “A divide-and-rule scheme for shot boundary detection based on sift.” Journal of Digital Content Technology and its Applications (2010): 202–214. ↩︎

Apostolidis, E. & Mezaris, V. “Fast shot segmentation combining global and local visual descriptors.” In: International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing , Florence, Italy (2014), pp. 6583-6587. ↩︎

Xu, J., Song, L., & Xie, R. “Shot boundary detection using convolutional neural networks.” In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Visual Communications and Image Processing (2016), pp. 1-4. ↩︎

Gygli, M. “Ridiculously Fast Shot Boundary Detection with Fully Convolutional Neural Networks.” In: International Conference on Content-Based Multimedia Indexing , La Rochelle, France (2018), pp. 1-4. ↩︎

Baraldi, L., Grana, C., & Cucchiara, R. “Shot and scene detection via hierarchical clustering for re-using broadcast video.” In: International Conference on Computer Analysis of Images and Patterns (2015), pp. 801-811. ↩︎

Baraldi, L., Grana, C., & Cucchiara, R. A “Deep Siamese Network for Scene Detection in Broadcast Videos.” In Proceedings of the 23rd Annual ACM Conference on Multimedia Conference , Brisbane, Australia (2015), pp. 1199-1202. ↩︎

Nguyen, B. T., Laurendeau, D., & Albu, A. B. “A robust method for camera motion estimation in movies based on optical flow.” IJISTA , 9(3/4) (2010): 228-238. ↩︎

Zhou, T., Brown, B., Snavely, N. & Lowe, D. G. “Unsupervised learning of depth and ego-motion from video.” In: Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (2017), pp. 6612-6619. ↩︎

Yin, Z. & Shi, J. “GeoNet: Unsupervised Learning of Dense Depth, Optical Flow and Camera Pose.” In: Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (2018), pp. 1983-1992. ↩︎

Ranjan, A., Jampani, V., Balles, L., Kim, K., Sun, D., Wulff, J. & Black, M. J. “Competitive Collaboration: Joint Unsupervised Learning of Depth, Camera Motion, Optical Flow and Motion Segmentation.” In: Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (2019), pp.12240-12249. ↩︎

Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I., & Hinton, G. E. “ImageNet Classification with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks.” In: Proc. of 26th Conf. on Neural Information Processing Systems 2012 . Lake Tahoe, Nevada, United States (2012), pp. 1106–1114. ↩︎

Girshick R. B., Donahue, J., Darrell, T., & Malik, J. “Rich Feature Hierarchies for Accurate Object Detection and Semantic Segmentation.” In Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition , Columbus, OH, USA (2014), pp. 580-587. ↩︎

Girshick, R. B. “Fast R-CNN.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computer Vision , Santiago, Chile (2015), pp. 1440-1448. ↩︎

Ren, S., He, K., Girshick, R., B., & Sun, J. “Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks.” Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence , 39(6) (2017): 1137-1149. ↩︎

Lin, T., Maire, M., Belongie, S. J., Hays, H., Perona, P., Ramanan, D., Dollár, P., & Zitnick, L. “Microsoft COCO: Common Objects in Context.” In: Proceedings of ECCV (2014), pp. 740-755. ↩︎

He, K., Gkioxari, G., Dollár, P., & Girshick, R. B. “Mask R-CNN.” In International Conference on Computer Vision , Venice, Italy (2018), pp. 2980-2988. ↩︎

Redmon, J. & Farhadi, A. “YOLO9000: Better, Faster, Stronger.” In: Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition , Honolulu, HI, USA (2017), pp. 6517-6525. ↩︎

Redmon, J. & Farhadi, A. “YOLOv3: An Incremental Improvement.” CoRR abs/1804.02767 (2018). ↩︎

Deng, J., Dong, W., Socher, R., Li, L., Li, K., & Fei-Fei, L. “ImageNet: A large-scale hierarchical image database.” In: Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (2009), pp. 248–255. ↩︎

Zhou, B., Lapedriza, A., Xiao, J., Torralba, A., & Oliva, A. “Learning Deep Features for Scene Recognition using Places Database.” In: NIPS Proceedings , Montreal, Quebec, Canada (2014), pp. 487-495. ↩︎

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., & Sun, J. “Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition.” In Proceedings of CVPR (2016), pp. 770-778. ↩︎ ↩︎

Liu, C., Zoph, B., Shlens, J., Hua, W., Li, L., Fei-Fei, L., Yuille, A., Huang, J., & Murphy, K. Progressive Neural Architecture Search (2017). ↩︎

Szegedy, C., Ioffe, S., & Vanhoucke, V. “Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the Impact of Residual Connections on Learning.” CoRR abs/1602.07261 (2016). ↩︎

Taigman, Y., Yang, M., Ranzato, M., & Wolf, L. “DeepFace: Closing the Gap to Human-Level Performance in Face Verification.” In: Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition , Columbus, OH, USA (2014), pp. 1701-1708. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Mühling, M., Korfhage, N., Müller, E., Otto, C., Springstein, M., Langelage, T., Veith, U., Ewerth, R., & Freisleben, B. “Deep learning for content-based video retrieval in film and television production.” Multimedia Tools Appl. 76(21) (2017): 22169-22194. ↩︎

Hays, J. & Efros, A. A. “IM2GPS: estimating geographic information from a single image.” In Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition , Anchorage, Alaska, USA (2008). ↩︎

Hays, J. & Efros, A. A. “Large-Scale Image Geolocalization.” Multimodal Location Estimation of Videos and Images (2015): 41-62. ↩︎

Vo, N., Jacobs, N., Hays, J. “Revisiting IM2GPS in the Deep Learning Era.” In: International Conference on Computer Vision (2017), pp. 2640-2649. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Weyand, T., Kostrikov, I., & Philbin, J. “PlaNet - Photo Geolocation with Convolutional Neural Networks.” In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision , Amsterdam, The Netherlands (2016), pp. 37-55. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Seo, P. H., Weyand, T., Sim, J., & Han, B. “CPlaNet: Enhancing Image Geolocalization by Combinatorial Partitioning of Maps.” In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision , Munich, Germany (2018), pp. 544-560. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Müller-Budack, E., Pustu-Iren, K., & Ewerth, R. “Geolocation Estimation of Photos Using a Hierarchical Model and Scene Classification.” In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision , Munich, Germany (2018), pp. 575-592. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Palermo, F., Hays, J., & Efros, A. A. “Dating Historical Color Images.” In: Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision , Florence, Italy (2012), pp. 499-512. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Müller, E., Springstein, M., & Ewerth, R. “ When Was This Picture Taken? - Image Date Estimation in the Wild.” In: Proceedings of the European Conference on IR Research , Aberdeen, UK (2017), pp. 619-625. ↩︎ ↩︎

Ewerth, R., Springstein, M., Phan-Vogtmann, L. A., & Schütze, J. “ Are Machines Better in Image Tagging? – A User Study Adds to the Puzzle.” In: Proceedings of 39th European Conference on Information Retrieval (ECIR) , Aberdeen, UK (2017), pp. 186-198 ↩︎

Jiang, Y. G., Ye, G., Chang, S. F., Ellis, D., & Loui, A. C. “Consumer video understanding: a benchmark database and an evaluation of human and machine performance.” In: Proceedings of the International Conference on Multimedia Retrieval (2011), p. 29. ↩︎

Parikh, D. & Zitnick, C. L. “The role of features, algorithms and data in visual recognition.” In: Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (2010), pp. 2328–2335. ↩︎

Xiao, J., Hays, J., Ehinger, K. A., Oliva, A., & Torralba, A. “SUN database: large-scale scene recognition from abbey to zoo.” In: Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (2010), pp. 3485–3492. ↩︎

Szegedy, C., Liu, W., Jia, Y., Sermanet, P., Reed, S., Anguelov, D., Erhan, D., Vanhoucke, & V., Rabinovich, A. “Going deeper with convolutions.” In Proceedings of the Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (2015), pp. 1–9. ↩︎ ↩︎

He, K., Zhang, X., Ren, S., & Sun, J. “Delving Deep into Rectifiers: Surpassing Human-Level Performance on ImageNet Classification.” In Proceedings of ICCV (2015), pp. 1026-1034. ↩︎

Schroff, F., Kalenichenko, D., & Philbin, J. “FaceNet: A unified embedding for face recognition and clustering.” In: Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition , Boston, MA, USA (2015), pp. 815-823. ↩︎ ↩︎

Phillips, P. J., Scruggs, W. T., O’Toole, A. J., Flynn, P. J., Bowyer, K. W., Schott, C. L., & Sharpe, M. FRVT 2006 and ICE 2006 Large-Scale Results (2006). ↩︎

Junkerjürgen, R. Spannung – narrative Verfahrenweisen der Leseraktivierung: eine Studie am Beispiel der Reiseromane von Jules Verne. Frankfurt am Main; Berlin; Bern; Bruxelles; New York; Oxford; Wien: Lang (2001). ↩︎

Weibel, A. Spannung bei Hitchcock. Zur Funktionsweise auktorialer Suspense . Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann (2008). ↩︎

Weibel, A. Suspense im Animationsfilm Band I Methodik: Grundlagen der quantitativen Spannungsanalyse. Studienbeisipiel Ice Age 3 . Norderstedt: Books on Demand (2017). ↩︎

Huff, M., Meitz, T., & Papenmeier, F. “Changes in Situation Models Modulate Processes of Event Perception in Audiovisual Narratives.” Journal of Experimental Psychology - Learning, Memory, and Cognition , 40(5) (2014): 1377-1388. ↩︎