Medieval manuscript descriptions and the Semantic Web: analysing the impact of CIDOC CRM on Italian codicological-paleographical data

1. Introduction

European medieval manuscripts represent one of the most significant treasures of human culture and society, revealing rich information about the past that is invaluable to historical research. History, art history, literature and philology, codicology and palaeography, all rely on the analysis of manuscripts, and scholars in these disciplines engage with these objects in unique ways. However, whether the main focus may be the handwritten document in its physicality or the textual content of the manuscript, “‘the first level of enquiry always is (or should be) the document, the physical support that lies in front of the scholar’s eyes’” 1. The physical — i.e. codicological and palaeographical — details of a manuscript play a pivotal role not only in the identification and study of the handwritten source, but also enable the scholar to reconstruct a particular social and cultural context. Research related to handwritten primary sources is thus dependent on the descriptions of manuscripts. These descriptions aim to provide a faithful reconstruction of a manuscript by expressing its formal structure in a technical language also made of abbreviations and formulae 2. According to Italian cataloguing practice, after a first outline of the external facies each description should delineate the history of the codex, the texts contained within it and finally the bibliography for research on the manuscript 2.

Today, XML-encoded analytic descriptions of the physical and intellectual nature of manuscripts work as digital surrogates of these artifacts while enabling the knowledge contained in these descriptions to be interrelated and thus potentially compared by users. Indeed, as stressed by Stinson 3, the purpose of the cataloguing itself has slightly changed with its translation to the digital environment. In a setting where facsimile images can be often accessed to visualise the original artifacts, descriptions have gained a new level of usefulness: they serve as “a means for sorting, classifying, and comparing collections of manuscripts” 3 because, even when digital images are available to scholars, “without metadata, there is no access and no meaning” 4. The result of the online descriptive records is that hypertext information is now searchable, potentially linked, making comparisons among manuscripts easier. However, the interrelation of intellectual objects “requires creating explicit machine-readable data that allow automated correlation or collocation of related resources” 5. European cultural heritage institutions recognise the need to create metadata; nevertheless, the lack of automated correlation is a major challenge to the creation of timely and granular metadata for medieval manuscript descriptions. Specifically, the heterogeneity of codicological-paleographical records in terms of metadata and terminology is weakening the integration and interoperability within the community.

This paper6 focuses on one approach that has been proposed against this unstandardised setting: the Semantic Web addresses metadata automation because of its potential to leverage ontologies as means to more effectively connect medieval manuscript data according to its semantics. At present, although the valuable role of computational ontologies is getting interest in the broader Humanities, the employment of these recent developments in knowledge representation is still narrow in the field of medieval manuscript descriptions, which always require an “ad hoc” consideration due to the peculiar data they examine 7. Against this scenario, this paper concentrates on primary sources coming from the Middle Ages, and it explores the impact of a top-level ontology designed for modelling cultural objects, namely CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model , on a specific set of Italian manuscript descriptions. Though limited in the extent of its examination, this case study attempts to add evidence and potentially further the analysis and implementation of ontologies on codicological-paleographical catalogue records.

2. Medieval manuscript descriptions: an unstandardised setting

Metadata standards

Medieval manuscripts can be described within general databases, such as a library’s collection database, or specific manuscript databases. In the former context, records about a collection of manuscripts might be encoded in bibliographic technical and structural standards, as – for example – MARC 21 Format for Bibliographic Data or UNIMARC . In contrast, most of the significant European catalogues use the Text Encoding Initiative ( TEI P5 ) standard to encode metadata about their medieval manuscripts. Specifically, the TEI Manuscript Description element (

Granularity of the records

The semantic and syntactical nature of XML provides many opportunities for encoding granular and extensible records, which offers many unique opportunities for data about medieval manuscripts. Moreover, the TEI

Terminology

TEI is a complex schema, which means, to analyse TEI records, we need a clear understanding of elements and terminology. A first level of inconsistency depends on the variety of data schemas that can be adopted in this domain: some TEI elements could be similar to those of a customized data structure or the MARC 21 standard, but they may not use the exact same terms. Taking into account how multilingualism complicates this framework on a further level 9 10 11. The language of manuscript catalogues varies from country to country; furthermore, expert palaeographers tend to make terminological choices according to their sub-domains and contexts 12 2, consequently causing an heterogeneous and unstandardised vocabulary in terms of handwriting.

Encoding methods in TEI standard

Barbero and Trasselli 13 highlighted critical aspects about the encoding of some codicological data in TEI format. According to their analysis, when creating records for manuscripts material, the number of folios and size of leaves are particularly exposed to differences in description. Furthermore, they emphasized that a single procedure about how to structure each information is not provided by the TEI Guidelines and this factor represents an obstacle towards the desirable data sharing.

3. Current proposals: Semantic Web and ontologies

Research on Semantic Web technologies has produced insights into the challenges associated with standardizing metadata for manuscripts. In particular, the application of ontologies in the domain of codicological and paleographical data has been evaluated as a clever approach towards better communication within the community. A clarification about what ontology means in this context, and its relation with the Semantic Web and Linked Data, constitutes a preliminary step in understanding which benefits ontologies can offer to the complex framework outlined in Section 2.

The word ontology in a computational sense is derived from a long established tradition in the philosophical field, namely the concept - introduced by Aristotle - of “a particular system of categories accounting for a certain vision of the world” 14. Though preserving a close link to its source, the computer science community has adapted the term to the digital environment to describe an engineering artifact which can be defined as a “formal, explicit specification of a shared conceptualisation” 15. Conceptualisation is the backbone of an ontology 16: consisting of an abstract model of the state of affairs of a certain area of interest, an ontology takes the objects, concepts and other relevant entities of this area and it explicitly defines them and the relationships among them17 . In order to be called ontology, the model needs to reflect “‘a certain rate of consensus about the knowledge in that domain’” 15, and therefore to express a view accepted by that specific community rather than by an individual. Finally, the ontology has to be given in a formal language, that is in a machine-readable format. The overall result is a set of logical axioms usually based on the so-called Description Logics, a formal language for the knowledge representation that gives the capability of deducing new information from an explicated group of data 18. As a consequence of the aforementioned logical foundations, information integration and exchange are the main valuable tasks that ontologies can perform. They capture and model a shared understanding of a domain, making explicit the inherent semantics and thus avoiding ambiguous meanings. In doing so, they act as a medium for knowledge sharing and communication not only among resources of an area but also over different systems.

Thanks to their nature, ontologies have played a fundamental role in the development of the Semantic Web. The concept of the Semantic Web, or “Web of Data” 19, was publicly conceived in the early 2000s as an extension of the World Wide Web able to automatically read and process data and information without human intervention 20. From the very first, the essential requirement for this task was that the meaning — i.e. the semantics — of Web data should have been explicated in a machine-readable format in order to allow computers to discover, manipulate and link information from heterogeneous sources 21. Ontologies thus became a basic component of the Semantic Web, since they provide meaningful identifications of concepts and relationships and help data to be powerfully searched, integrated and exchanged 22. The achievement of such a framework needed a set of established standards and technologies to create relationships among different datasets and thus formally explain computers how to access and associate the information 23 24. The term Linked Data refers to this technical set.

The role of the ontologies of sharing a common knowledge representation and rendering “domain assumptions explicit” 25 has been assessed by Burrows 9 and Kummer 11 a significant opportunity to enhance the interoperability and connection in the body of knowledge of medieval manuscripts. Albeit referring to a broader range than the single manuscript descriptions, in Burrow’s opinion the coexistence of different data structure standards could be overcome by making explicit the semantic categories (as names, concepts, events) embedded in resources about manuscripts. Unique identifiers for each of these entities could allow an interlinked environment where data within heterogeneous resources point to them. Envisioning which contribution the Semantic Web could bring to codicology, Kummer has discussed a similar approach. He has considered how the application of a specific ontology designed within the cultural heritage, the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model ( CIDOC CRM ), could integrate data and “support communication processes” 11. The fact that CIDOC CRM concentrates “on contextualization of objects” 11 and allows different opinions and uncertain information to be encoded together, has been argued to fit well with the codicological framework. In regard to the first aspect, the core of this ontology is indeed represented by the events, a basic concept which allows to integrate facts, objects, actors, places 26.

In the same way, the terminological aspect which challenges the medieval manuscripts area has found in the Semantic Web techniques a possible resolution. Whether considering the perspective of multiple national languages or recognising that an established palaeographical vocabulary still misses, scholars seem to agree that an ontology could represent a valuable answer because it could be able to align different vocabularies in a conceptual map 9 12 11 8. In two cases the SKOS standard has been suggested as the appropriate format for this mapping.

Although many points of analysis could have been explored in the research area of this paper, Kummer’s proposal of testing the suitability of CIDOC CRM to codicological data was particularly taken into account. Indeed, it was investigated how CIDOC CRM could address some of the challenges that Section 2 has outlined. Section 4 illustrates this introductory analysis in more detail.

4. A case study: methodological premises and approach

4.1. ManusOnLine and two “special projects”

ManusOnLine (or MOL ) constitutes the outcome of the most significant Italian proposal towards a standardised manuscript cataloguing. Inaugurated in 2007, it is the first Italian online software developed for the encoding of manuscript descriptions 13 27 28. To date, 415 cultural heritage institutions use this relational database to create descriptions of their manuscripts and make freely accessible their data on the web, in some cases also providing digital images. In order to provide libraries and research institutions with the same data they have produced, in 2012 MOL then developed an application to export manuscript descriptions as TEI XML files.

Taking into account the more complex and various European settings previously described, it could be properly argued that the focus on a single schema and encoding method challenges the validity of the outcomes of an ontology implementation. It is thus important to stress some considerations. On the one hand, scholars’ judgements on the appropriateness of TEI in this domain were considered as an argument in favour of the first aspect. Moreover, as it will be further presented, a special research has been started about the harmonization between TEI and CIDOC CRM (see Section 5.2). In view of CIDOC CRM as the ontology selected for this case study, this was viewed as an additional reason. On the other hand, a uniform encoding method was preferred according to the necessity of a homogeneous corpus on where to focus the analysis. A level of variety, although different, was intended to be added by the following characteristic.

MOL provides a further grade of cooperation. It allows specialised research projects to use its software for the cataloguing while consenting them to keep a total autonomy in the management of their records 29. Two of these projects which are collaborating with MOL are Censimento Internazionale Manoscritti Francescani ( International Census of Franciscan Manuscripts ), and the Illuminated Dante Project (or IDP ). The first one, supervised by the International Society of Franciscan Studies of Assisi , aims to gather together the textual tradition of the thirteenth-fourteenth century Franciscan sources belonging to different literary genres and hold in Italian and foreign cultural institutions 29. Alternatively, the IDP will create by 2021 the most comprehensive online archive of those manuscripts of Dante’s Divine Comedy containing illustrations and dating to the fourteenth-fifteenth centuries. This archive will provide their codicological and iconographic descriptions as well as high-definition images 30 31.

Commonly, the granularity and depth of descriptions is influenced by the decisions made by each project’s cataloguers: the general guiding purpose affects the meticulousness of the cataloguing activity. These two projects can represent two examples: whereas IDP is based on thorough and complete first-hand descriptions that have required the supplement of new codicological-paleographical fields in MOL 30, the International Census of the Franciscan Manuscripts is only focused on the digitisation of existing printed catalogues 29, often quite dated. It is also noteworthy to emphasise that, since it is a database for manuscripts in a broad extent, MOL itself allows a certain level of flexibility.

For the aspects aforementioned, the differences of these two special projects, while being founded on a common ground — i.e. MOL — assessed an interesting material on which to analyse the implementation of an ontology. This approach was led by the intent of collecting an “heterogeneous” dataset, although in a restricted sense, and disclosing the challenges that could emerge when dealing with singular documents as medieval manuscripts are. More precisely, the study was based on a subcorpus of fifteen manuscript descriptions belonging to both the projects (the list is provided in Appendix 3).

4.2. CIDOC CRM

CIDOC CRM is an ontology specifically devoted to the domain of cultural objects. As a result, CIDOC CRM presents a modelling design that attempts to address the challenges produced by this kind of object: “‘imprecision, vagueness, lacunae’” 32 as well as context-dependency and multiple interpretations.

Firstly, it is a top-level ontology, meaning that it delineates general classes and properties, as events, places, actors, “which are independent of a particular problem or domain” 14. However, in order to supply the needs of specific communities and applications, CIDOC CRM has been made potentially extensible. As many new sub-classes or sub-properties as required by each sub-domain can be added to the available classes and properties of the conceptual model 33. This theoretical ground is particularly relevant when explored by the perspective of manuscript descriptions. On the one hand, the core classes and properties which sit at the top of the ontology should be valid for all the records despite their divergence in the granularity. Equally, more detail can later be included in the ontology. On the other hand, as was stressed by Kummer 11, the possibility to incorporate different views on the same material is helpful for the uncertainty that in some cases affects the codicological-paleographical information, such as multi-interpretable dates or scribal hands.

Secondly, at the foundation of CIDOC CRM there is the aim of focusing on the semantics of data schemas, in particular the relationships that exist among the inherent concepts, rather than the terminology related to data encoded in these schemas 34. For this reason, classes referring to the terminology ( E41 Appellation ) have been distinguished from the concepts underlying data 33. The fact that medieval manuscript cataloguing often involves a significant diversification in the vocabulary, whether paleographical or simply linguistic, seems to find a support in CIDOC CRM ’s distinction between top-level semantics and terminology. Where an agreement on the terms to be used still misses, a correspondence between the concepts that sit behind those terms could instead be more easily obtained.

The implementation of CIDOC CRM sought to disclose to what extent the above articulated theoretical assumptions could be accepted within the constraints of the dataset selected as a case study. Nevertheless, the application and extension of an existing ontology on a specific dataset is a long and time-consuming work requiring great expertise both on the technologies and the domain knowledge of the materials. The approach which was undertaken within this case study should be thus rather viewed as an initial attempt which considered only the first step of this long process. Specifically, the semantics underlying the selected TEI XML -encoded manuscript descriptions of the International Census of the Franciscan Manuscripts and IDP were explored according to a subset of CIDOC CRM .

5. Implementing CIDOC CRM

5.1. Preliminaries

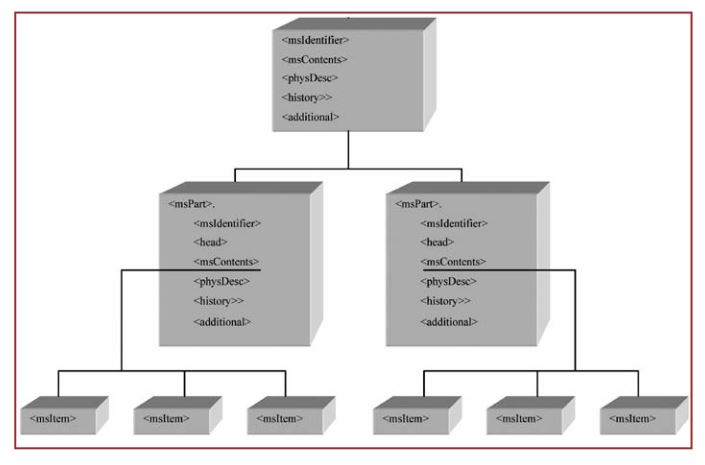

The implementation of an ontology should always start from defining “its domain and scope” 25. Answering the question “what knowledge do you want to represent” 35 thus corresponds to the first primary step that needed to be performed. Within the high-level element TEI

Once the decision about how general the ontology is going to be has been made, the desired information has to be mapped to the CRM classes and properties that best represent it 35 37. It is at this second stage of the process that the examination of the event-centric principle — on which CIDOC CRM is founded — produced a further consideration. As stressed by Doerr and Kritsotaki 38, the modelling of historical contexts in terms of events and processes can more effectively aggregate and link, through varied kinds of relationships, historical and cultural information. Indeed, history can be seen as a sequence of events “involving participation of people and things” 38 and the creation of cultural objects is placed within this process. It can be easily recognised that the same theoretical principle was not applied to the design of the TEI structure of a manuscript description. Within a TEI XML record, data related to the physical carrier, the intellectual content carried by it and the full historical process that brought a manuscript into existence is encoded separately. However, on the contrary, all this information overall composes a network of relationships: actors, materials, ideas have met in particular space-times and need to be linked in order to capture the historical context of a manuscript.

Macrostructure of the TEI manuscript description. [^barbero2013]

As a consequence, a conceptual re-arrangement of all the details contained in the manuscript descriptions was considered a pivotal step in order to more easily map the TEI metadata to CIDOC CRM ontology. In accordance with the CIDOC CRM event-modelling principle, the whole general sequence of activities which has as its outcome the current historical condition of a manuscript, both in its physical and intellectual nature, was split and analysed in its internal phases. The theoretical implementation of the ontology was performed according to this temporal order.

Regarding the practical mapping, CIDOC CRM does not provide any guidelines about how to integrate local schemas to the concepts defined in the ontology. The documentation of the standard only “defines the model on a purely conceptual level” 39. Confronting with this lack, a way of performing the alignment of metadata with the ontology is the creation of “mapping chains” (or paths), i.e. “sequence[s] of semantically associated [ CIDOC CRM ] classes and properties, representing a specific concept” 39. The binding of a manuscript – for example – can be represented by the following mapping chain: E12 Production - P108 has produced - E22 Man-Made Object - P2 has type - E55 Type : Binding . Within the framework of the analysed set of manuscripts, mapping paths were thus created for each concept occurring in each specific stage of the creation of a manuscript. While the chains are graphically displayed in Appendix 1, the table in Appendix 2 schematically presents them40 .

Finally, as previously delineated, CIDOC CRM is a potentially extensible ontology. In order to “preserve the original semantics and/or to uniquely identify the metadata information” 41 it allows – for instance – to sub-class existing classes. This sub-classing can be modelled through two approaches: by creating new sub-classes or by specialising and extending the class E55 Type 42 introducing a domain-specific vocabulary. The first method is by all means more elaborate; the latter is ontologically easier and more time-saving. Also bearing in mind the “[m]inimality modelling principle of CIDOC CRM ” 37 according to which a new class should be created only if it requires new additional properties, for this case study the second method was evaluated the most appropriate. In particular, the values of the instances of E55 Type were drawn from the terminology provided by Muzerelle 43. Although this online resource cannot be strictly considered a controlled vocabulary, it was positively assessed taking into account a possible multilingual integration of manuscript descriptions.

5.2. Mapping and its evaluation

Since 2004, a unit within the TEI Ontologies Special Interest Groups (SIGs) has been focused on the relationship between TEI and CIDOC CRM standards towards a mapping of the elements of the former with classes and properties of the latter 44 45 46 47 48. Specifically, it has been underlined the development from TEI P4 to TEI P5 in including “new elements for marking-up real-world information” 48, as – for instance –

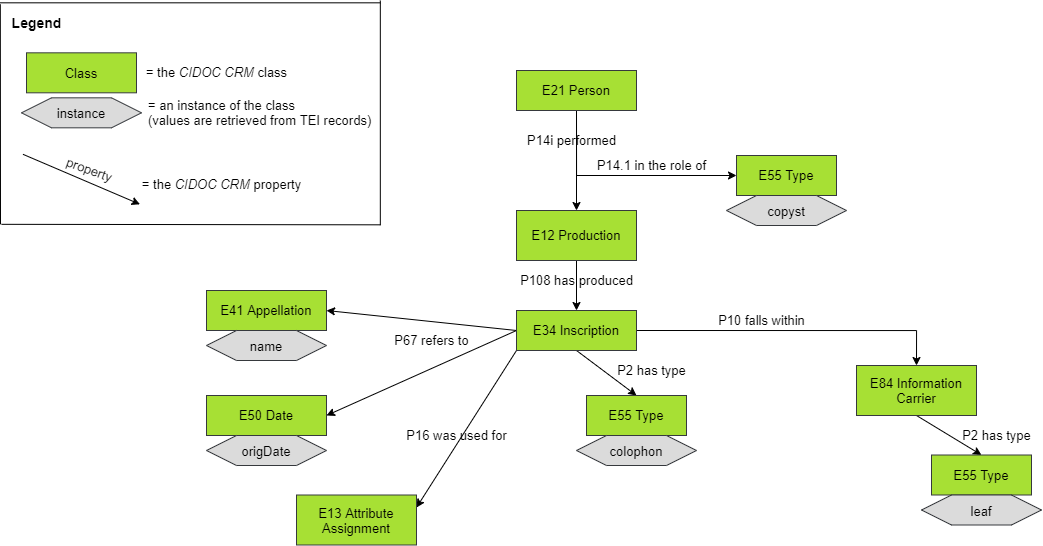

However, a manuscript description is a particular type of TEI document. It has been designed having in mind the implicit conceptual model at the base of the European cataloguing practice. Consequently, it can be inferred that each specialised TEI element has been introduced according to an agreed contextual meaning. Considering the XML structure of a manuscript description rather than its textual content, at least events and relations can be generally deduced although they are not expressively identified. The following example can serve as a better explanation. The identification of the copyist and especially the date of writing represent two of the main challenges faced by paleographers and codicologists when studying a manuscript 2. This is due to the fact that, in most of the cases, the transcription of a text was carried out anonymously, without any temporal indication. However, an exception to this status quo is represented by the colophon, i.e. an original date (and name) handwritten by the copyist on the leaves during the stage of the handwriting. For its inherent semantics, the presence of a colophon ( E34 Inscription ) means that this final formula was added by a person ( E21 Person ), i.e. the copyist, _ _ and it may contain information able to identify ( P67 refers to ) the date of writing and the copyist himself, helping the scholar to provide his own hypothesis on the manuscript ( P16 was used for - E13 Attribute Assignment ) (see Figure 2). Making explicit causal and temporal relationships, the overall mapping of the specific TEI records to CIDOC CRM was generally successful because of this aspect.

Modelling of a colophon.

The aforesaid reasoning needs further consideration, though. Events require to be placed in specific time frames and linked to identified actors in order to model factual information. If this data is not encoded in tags as

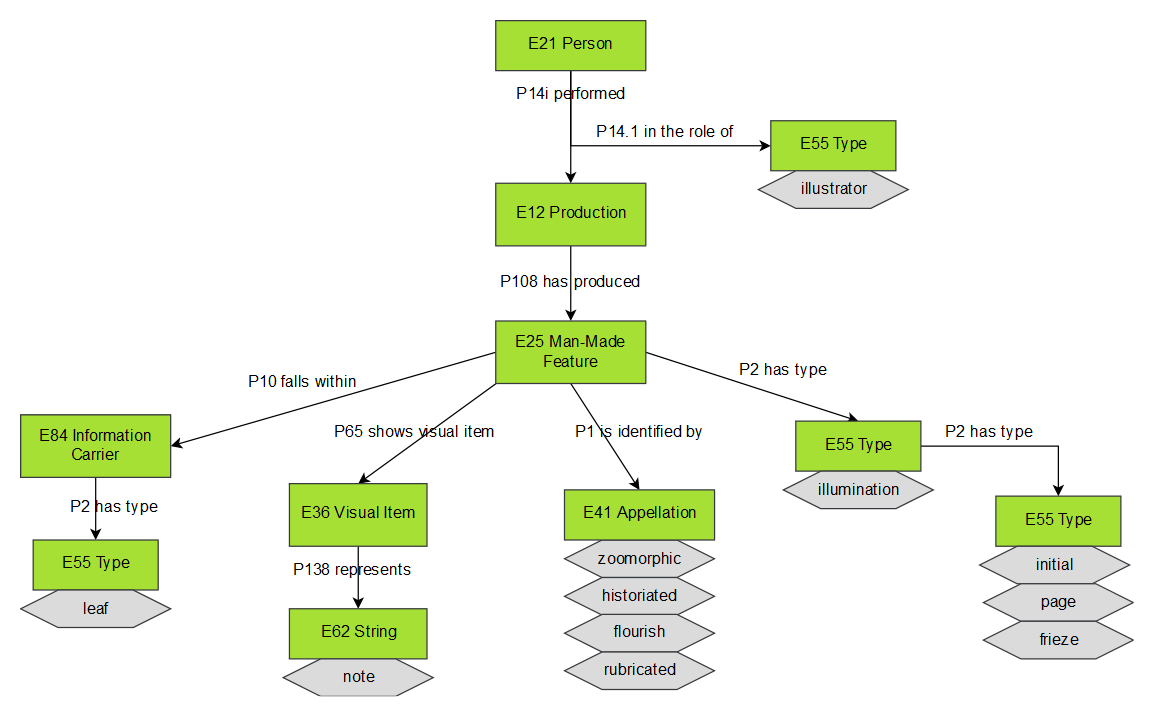

In reference to some of the aspects against which the choice of CIDOC CRM ontology was made, the described project was finally assessed as positive evidence. Firstly, the dissimilarities between bare and more accurate descriptions did not heavily affect the good outcome of the implementation. As a representative specimen, the conceptual identification of a comprehensive class for any kind of illumination occurring in a manuscript, distinct from its subtypes, allowed to model the different granularity of this category found in the analysed records. During the modelling, it was chosen to firstly sub-type the class E55 Type for classifying the physical feature holding the illumination, e.g. initial, leaf, frieze (encoded in the TEI @type attribute). Then, the class E41 Appellation was used to specify the conventional terms for describing a particular category (occurring in the TEI @subtype attribute), whose semantic meaning is explained by the class E36 Visual Item (see Figure 3).

Modelling of an illumination.

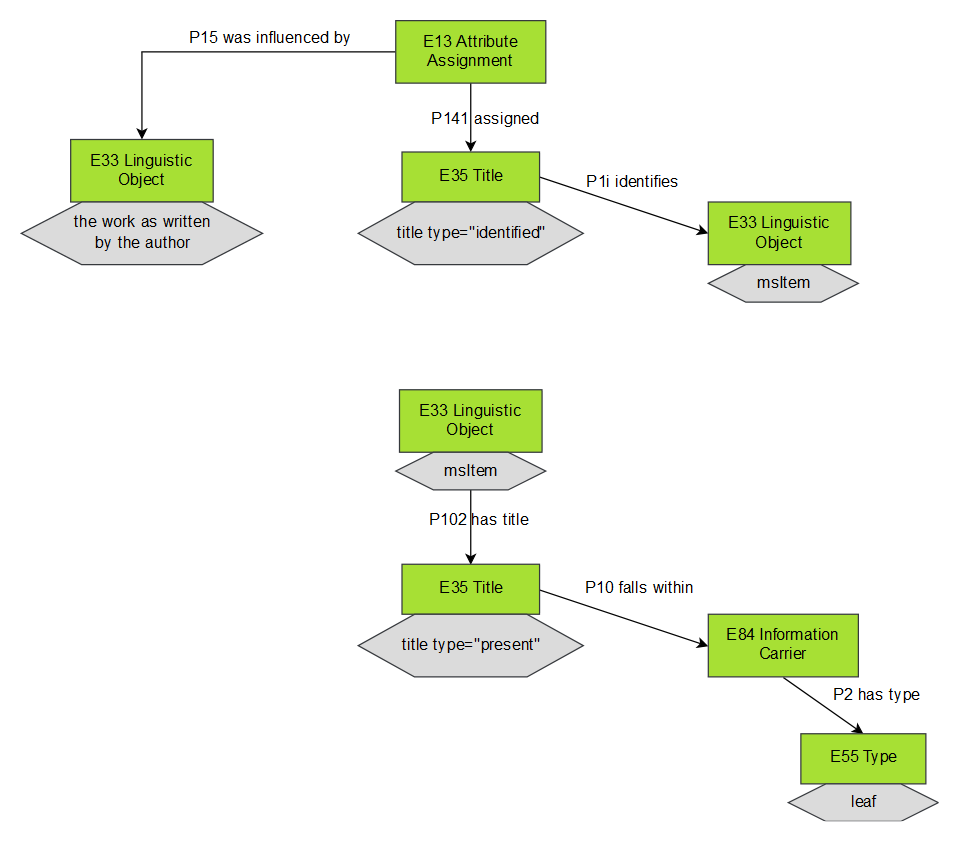

An additional level of evaluation pertains the contradictory views. CIDOC CRM ontology enabled to distinguish facts that were asserted by the handwritten sources from those that, although based on these sources, were only “exhibited in or presupposed” 49. An example is provided. Handwritten texts usually do not include titles, which thus need to be deduced through a scholar’s analysis of the content. However, it can happen that titles occur in a specific leaf and thus no interpretation is required. Two mappings of the title of a manuscript (see Figure 4) were thus needed in order to make a clear distinction between the factual and interpretative nature of information.

Different mappings for the two types of title.

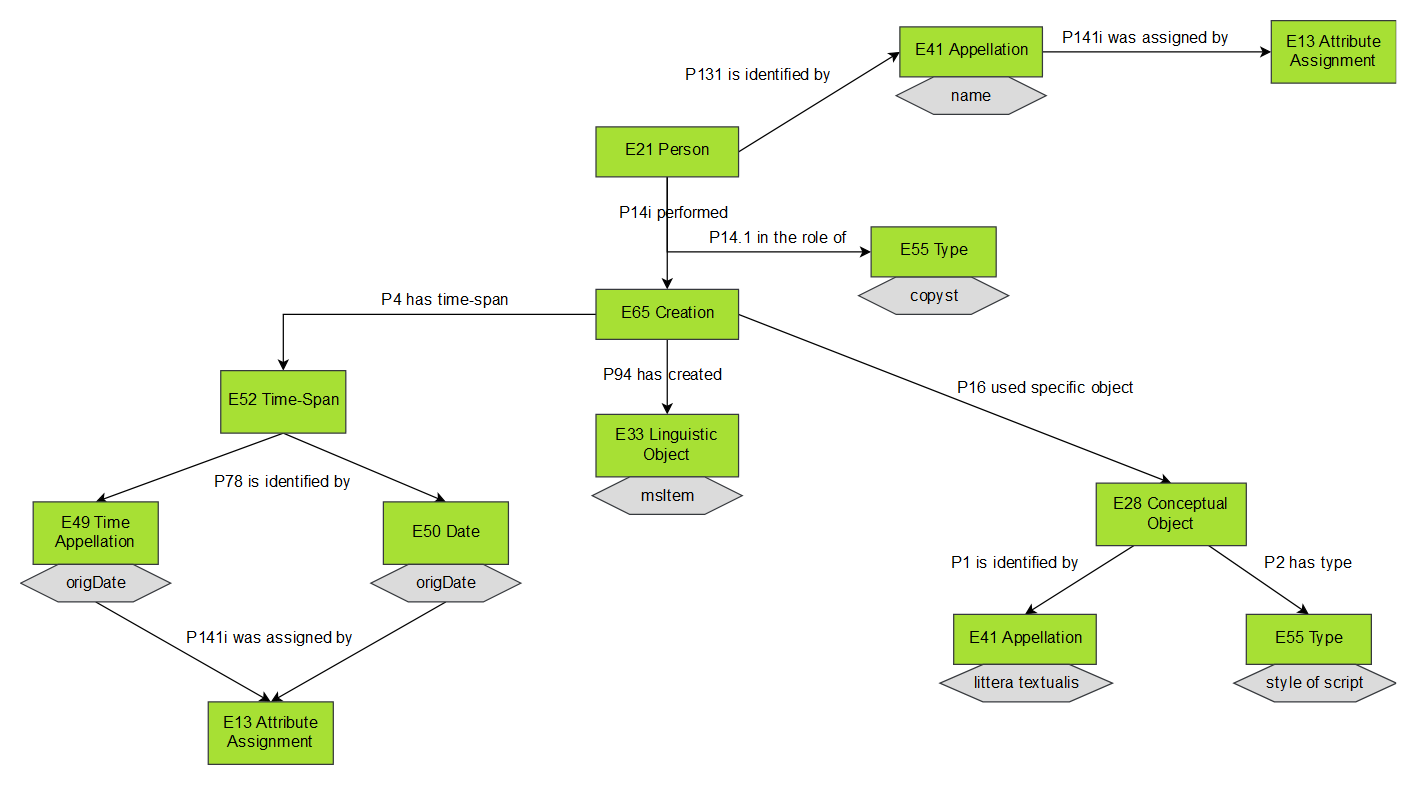

Lastly, the use of the class E55 Type for representing the concepts of a codicological thesauri and the use of E41 Appellation for naming instances of classes “by convention, tradition, or agreement” 34 showed that the distinction between concepts and terminology is actually possible. According to this principle, in the context of an heterogeneous vocabulary for handwriting scripts, it was possible to keep separate the concept of the style of script ( E55 Type) from – for example – the conventional name littera textualis ( E41 Appellation) (see Figure 5).

Part of the modelling of the handwriting of the texts.

6. In the “real world” : broader considerations

The analysis presented in this paper was not performed on a comprehensive range of medieval manuscript descriptions encoded in different metadata schemas, neither did it involve the implementation of an ontology in all its required stages. If so, these choices would have let results have a more authoritative voice, highlighting at the same time a major level of complexity that the “real world” necessarily involves. The following paragraphs aim to introduce this broader context, stressing a potential affinity with other areas facing similar challenges.

Just considering TEI standard, individual customisations of the TEI P5 manuscript description module would be the first hurdle to deal with during the investigation of heterogeneous manuscripts data. The proposal by Page et al. 50 of an intermediate, simplified and more rigid XML file, i.e. a selected list of metadata fields coming from an overall analysis of the source records, could be assessed as a feasible approach, representing a form of standardization where to focus the mapping to the ontology. Nevertheless, whatever workflow is chosen, the engagement of experts in expressing the processes and methods they used for encoding their data remains pivotal. Institutions who “precisely know the semantic definitions” of their schemas 39 “‘must be involved in encoding the meaning of their own information’” 51. Equally, corporate bodies’ commitment to provide Linked Data versions of manuscript data should take into account the “semantic enrichment” 52 of their datasets values by linking their data to external authority files and controlled vocabularies. A web platform as the one developed by the symogih.org project 53 might be seen as the most straightforward path to this envisioned framework. In this user-friendly environment, data providers would be allowed to annotate their descriptions as well as to represent the embedded knowledge of their data structures “encoding knowledge units directly into texts” 53 — i.e. linking TEI tags to classes and properties of a CIDOC CRM -based ontology. On top of this platform a portal should then be implemented for exploring, searching and discovering the harmonized datasets and records. Nonetheless, all these infrastructural components would require noticeable long-term and large-scale efforts. As emphasized by Burrows, much more work on Linked Open Data has been made in the fields of Classics, Ancient History and LAM community, bringing into existence significant collaborative annotation platforms as Pelagios or Perseus Digital Library , whereas “this kind of framework for linking disparate resources is lacking for medieval and Renaissance studies” 54.

Despite the above-mentioned considerations, the challenges in terms of infrastructure as well as human and economic resources should not overcome the potential benefits that such an implementation could involve. The introductory paragraphs of this article have underlined how “manuscripts form a crucial evidence base for the humanities, and research into their histories has important benefits for a wide range of disciplines” 54, from social science to art history. The recognition of different scribal hands in the same manuscript – for instance – can help the understanding of its genesis and transmission, telling insightful knowledge about the monastery in which it was firstly written, its spheres of influence and its links. On the other hand, a valuable binding and a large presence of illuminated letters can reveal something about the social status of the family by whom the codex was commissioned. The possibility of searching across disparate databases on a single platform – thanks to semantic relationships such as those defined by CIDOC CRM – would enhance the quality, in terms of both discovery and analysis, of a great variety of large-scale qualitative investigations which researchers could be focused on.

7. Conclusions

Semantic Web technologies provide the ability to more effectively connect and integrate structured data by disclosing their intended meaning and therefore making explicit their description, context and provenance. While allowing integration and interoperability across heterogeneous resources, one great benefit of the Semantic Web is that the local meaning of each of these resources is never lost and the source systems are not demanded for large changes: “semantics can be embedded (rather than described separately) within exactly the same structure” 51. Within the context of medieval manuscript descriptions, the implementation of ontologies can represent a valuable enhancement of manuscript research. A growing number of semantically interlinked and automatically discoverable descriptions, though encoded by different institutions in a variety of standards and vocabularies, could firstly enable researchers to extend their query and thus their range of observation. At the same time, the unlimited retrieval of information could make scholars face unplanned discussions and questions.

The case study presented in this paper has been focused on one specific instance of medieval manuscript data lacking explicit semantics: the paleographical-codicological descriptions belonging to two different collections within the Italian catalogue ManusOnLine . The disclosing of relationships and concepts embedded in the tags of the analysed TEI records revealed that a deep domain-specific knowledge, i.e. the process of the creation of a manuscript and its involved terminology, is essential towards an effective mapping of this data to an ontology. Along with this, bringing under scrutiny the TEI encoding of data and the context of this information led to discerning, in an epistemological process, factual from categorical data. It has been also emphasized how abstract entities and properties of the suggested CIDOC CRM ontology allow individual interpretations.

Taking into account the limitations of this case study and its challenges, this initial theoretical attempt towards the proposed solution of the Semantic Web technologies to integrate an heterogeneous framework, as that of medieval manuscript descriptions, can be positively evaluated. However, there are still many problems that need to be addressed if considering a real-world implementation. But despite current and potential questions that demand to be investigated, tools are now available to achieve the promising outcome illustrated in the first paragraph of this conclusion. It remains to invest in Digital Humanities research and the cultural community in terms of interest, skills and collaborative work.

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

Appendix 3

Acknowledgements

A pivotal thank you to Dr. Kristen Schuster for the great encouragement and enthusiastic support in writing this article.

Pierazzo, E., and Stokes, P. (2010). Putting the Text back into Context: A Codicological Approach to Manuscript Transcription. In: Fischer, F., Fritze, C., Vogeler, C., 2011. Kodicologie und Paläographie im digitalen Zeitalter 2 (Codicology and palaeography in the digital age 2) , Schriften des Instituts für Dokumentologie und Editorik. Books on Demand (BoD), Norderstedt, pp.397-429. ↩︎

Petrucci, A. (1984). La descrizione del manoscritto. Storia, problemi, modelli . 1st ed. Urbino: La Nuova Italia Scientifica. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Stinson, T. (2009). Codicological Description in the Digital Age. In: Assmann, B., Rehbein, M., 2009. Kodicologie und Paläographie im digitalen Zeitalter (Codicology and palaeography in the digital age) , Schriften des Instituts für Dokumentologie und Editorik. Books on Demand (BoD), Norderstedt, pp.309-338. ↩︎ ↩︎

Fabian, C. (2016). RDA as a New Starting Point for International Cooperation: Retrospective National Bibliographies and Medieval Manuscripts. Cataloguing & Classification Quarterly , 54 (5-6), pp.338-349. ↩︎

Pitti, D. V. (2004). Designing Sustainable Projects and Publications. In: S. Schreibman, R. Siemens and J. Unsworth, eds. 2004. A Companion to Digital Humanities . Oxford: Blackwell. ↩︎

Barbero, G. (2013). Manoscritti e standard. DigItalia . <http://digitalia.sbn.it/article/view/824>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎

Uhlíř, Z. and Knoll, A. (2009). Manuscriptorium Digital Library and ENRICH Project: Means for Dealing with Digital Codicology and Palaeography. In: Assmann, B., Rehbein, M., 2009. Kodicologie und Paläographie im digitalen Zeitalter (Codicology and palaeography in the digital age) , Schriften des Instituts für Dokumentologie und Editorik. Books on Demand (BoD), Norderstedt, pp.67-78. ↩︎ ↩︎

Burrows, T. (2011). Applying Semantic Web Technologies to Medieval Manuscript Research. In: Fischer, F., Fritze, C., Vogeler, C., 2011. Kodicologie und Paläographie im digitalen Zeitalter 2 (Codicology and palaeography in the digital age 2) , Schriften des Instituts für Dokumentologie und Editorik. Books on Demand (BoD), Norderstedt, pp.117-131. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Humphrey, J. (2007). Manuscripts and Metadata: Descriptive Metadata in Three Manuscript Catalogs: DigCIM, MALVINE, and Digital Scriptorium. Cataloging & Classification Quarterly , 45 (2), pp.19-39. ↩︎

Kummer, R. (2011). Semantic Technologies for Manuscript Descriptions – Concepts and Visions. In: Fischer, F., Fritze, C., Vogeler, C., 2011. Kodicologie und Paläographie im digitalen Zeitalter (Codicology and palaeography in the digital age) , Schriften des Instituts für Dokumentologie und Editorik. Books on Demand (BoD), Norderstedt, pp.133-156. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Hassner, T., Rehbein, M., Stokes, P. A. and Wolf, L. (2012). Computation and Palaeography: Potentials and Limits. Dagstuhl Manifestos , 2 (1), pp.14-35. ↩︎ ↩︎

Barbero, G. and Trasselli, F. (2014-2015). Manus OnLine and the Text Encoding Initiative Schema, Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative . <https://jtei.revues.org/1054>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎ ↩︎

Guarino, N. (1998). Formal Ontology and Information Systems. In Proceedings of FOIS’98, Trento, Italy, 6-8 June 1998 , amended version. Amsterdam: IOS Press, pp.3-15. ↩︎ ↩︎

Studer, R., Benjamins, V. R. and Fensel, D. (1998). Knowledge Engineering: Principles and methods, Data & Knowledge Engineering . <http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0169023X97000566>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎ ↩︎

Guarino, N., Oberle, D., and Staab, S. (2009). What Is an Ontology?. In: S. Staab and R. Studer, eds. 2009. Handbook on Ontologies . Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp.1-17. ↩︎

Using the technical terminology, concepts are defined as classes and concrete examples of these concepts within a domain are called instances; relationships are named properties 56. ↩︎

Biagetti, M. T. (2016). Un modello ontologico per l’integrazione delle informazioni del patrimonio culturale: CIDOC-CRM, JLIS.it , 7 (3). <https://www.jlis.it/article/view/11930>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎

W3Cb (2015). Semantic Web . [web page] <https://www.w3.org/standards/semanticweb/> Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎

Berners-Lee, T., Hendler, J. and Lassila, O. (2001). The Semantic Web. Scientific American , May Issue. ↩︎

Hitzler, P., Krötzsch, M., Rudolph, S. (2010). The Quest for Semantics. In: P. Hitzler, M. Krötzsch and S. Rudolph, eds. 2010. Foundation of Semantic Web Technologies . Boca Raton: Chapman & Hall/CRC, pp.1-16. ↩︎

Taye, A. A. (2010). Understanding Semantic Web and Ontologies: Theory and Applications. Journal of Computing , 2 (6), pp.182-192. ↩︎

W3Ca (2015). Linked Data . [web page] <https://www.w3.org/standards/semanticweb/data>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎

Yoose, B., and Perkins, J. (2013). The Linked Open Data Landscape in Libraries and Beyond. Journal of Library Metadata , 13 (2-3), pp. 197-211. ↩︎

Noy, N. F. and McGuinness, D. L. (2001). Ontology Development 101: A Guide to Creating Your First Ontology . <https://protege.stanford.edu/publications/ontology_development/ontology101.pdf>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎ ↩︎

Doerr, M. (2003). The CIDOC Conceptual Reference Module: An Ontological Approach to Semantic Interoperability of Metadata, AI Magazine , 24 (3). <https://aaai.org/ojs/index.php/aimagazine/article/view/1720/1618>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎

Marcuccio, R. (2010). Catalogare e fare ricerca con Manus Online . < manus.iccu.sbn.it/upload/BibliotecheOggi_Marcuccio2010.pdf > . Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎

Merolla, L. and Negrini, L. (2014). Guida a ManusOnLine (MOL) - Standard per la catalogazione dei manoscritti delle biblioteche italiane . <www.iccu.sbn.it/opencms/export/sites/iccu/documenti/2014/GUIDA_MOLsettembre_2014.pdf>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎

ICCU. (2017). Manus OnLine . <http://manus.iccu.sbn.it/index.php?lang=en>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Illuminated Dante Project (IDP): Una startup per la digitalizzazione e l’analisi della più antica iconografia dantesca (secc. XIV-XV) . Venezia (2016). <http://www.iccu.sbn.it/opencms/export/sites/iccu/documenti/2016/V_CONVEGNO_ANNUALE_DELLxAIUCD_Panel_IDP.pdf>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎ ↩︎

IDP. (2017). Illuminated Dante Project . <http://www.dante.unina.it/public/frontend/index/language/en>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎

Zöllner-Weber, A. and Apollon, D. (2008). The challenge of modelling information and data in the humanities. In: T. Hug, Media, Knowledge & Education – Exploring new Spaces, Relations and Dynamics in Digital Media Ecologies . Innsbruck, Austria 25-26 June 2007. Innsbruck: Innsbruck University Press. ↩︎

Stead, S. (2008). The CIDOC CRM, a Standard for the Integration of Cultural Information . <http://old.cidoc-crm.org/cidoc_tutorial/index.html>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎ ↩︎

ICOM/CIDOC CRM Special Interest Group. (2017). Definition of the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model . Version 6.2.2. <http://www.cidoc-crm.org/sites/default/files/2017-09-30%23CIDOC%20CRM_v6.2.2_esIP.pdf>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Hiebel, G., Hanke, K. and Hayek, I. (2010). Methodology for CIDOC CRM based data integration with spatial data. In: CAA’ 2010 Fusion of Cultures, Proceedings of the 38 th _ Conference on Computer Applications and Quantitative Methods in Archaeology_ . Granada, Spain April 2010. ↩︎ ↩︎

This element has been excluded from the proposed mapping process given its closer relation to the bibliographic than codicological-paleographical interest. ↩︎

Theodoridou, M., Bruseker, G., Daskalaki, M. and Doerr, M. (2016). Methodological tips for mappings to CIDOC CRM . <www.cidoc-crm.org/sites/default/files/CAA2016MethodologicalTipsForMappingsToCIDOC-CRM-v4.pptx>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎ ↩︎

Doerr, M. and Kritsotaki, A. (2006). Documenting Events in Metadata. <http://www.cidoc-crm.org/sites/default/files/Documenting%20Events%20in%20Metadata.pdf>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎ ↩︎

Nussbaumer, P., Haslhofer, B. and Klas, W. (2010). Towards Model Implementation Guidelines for the CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model . <eprints.cs.univie.ac.at/58/1/nussbaumer10_cidoc_crm.pdf>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

It has to be stressed that the graphical representations illustrate in more detail the mapping, due to the complexity and large number of properties among entities. ↩︎

Nussbaumer, P. and Haslhofer, B. (2007). Putting the CIDOC CRM into Practice - Experiences and Challenges . <https://eprints.cs.univie.ac.at/404/>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎

This class is used to “characterize and classify instances of CRM classes” 34. ↩︎

Muzerelle, D. (2002). Vocabulaire codicologique : répertoire méthodique des termes français relatifs aux manuscrits . <http://vocabulaire.irht.cnrs.fr/pages/vocab2.htm>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎

Eide, O. (2010). Guidelines for the creation of TEI documents that will map well to ontologies such as the CIDOC-CRM. – Draft . <http://www.tei-c.org/SIG/Ontologies/guidelines/guidelinesTeiMappableCrm.html>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎

Eide, O. (2014-2015). Ontologies, Data Modeling, and TEI. Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative. <https://jtei.revues.org/1191>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎

Eide, O. and Ore, C.-E. (2006). TEI, CIDOC-CRM and a Possible Interface Between the Two. In: ACH and ALLC, Digital Humanities 2006 . Sorbonne, Paris, France, 5-9 July 2006. ↩︎

Eide, O. and Ore, C.-E. (2007). From TEI to a CIDOC-CRM Conforming Model: Towards a Better Integration Between Text Collections and Other Sources of Cultural Historical Documentation. <http://www.edd.uio.no/artiklar/tekstkoding/poster_156_eide.html>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎ ↩︎ ↩︎

Ore, C.-E. and Eide, O. (2009). TEI and cultural heritage ontologies: Exchange of information? Literary and Linguistic Computing , 24 (2), pp.161-172. ↩︎ ↩︎

Eide, O. (2008). The Exhibition Problem. A Real-life Example with a Suggested Solution. Literary and Linguistic Computing , 23 (1), pp.27-37. ↩︎

Page, K., Burrows, T., Hankinson, A., Holford, M., Morrison, A., Lewis, D. and Velios, A. (2019). A Layered Digital Library for Cataloguing and Research: Practical Experiences with Medieval Manuscripts, from TEI to Linked Data . In: Digital Humanities Conference 2019, 9 - 12 July 2019, Utrecht, the Netherlands. <http://ualresearchonline.arts.ac.uk/14433/>. Accessed 13 September 2019. ↩︎

Oldman, D., Doerr, M. and Gradmann, S. (2016). Zen and the Art of Linked Data: New Strategies for a Semantic Web of Humanist Knowledge. In: S. Schreibman, R. Siemens and J. Unsworth, eds. 2016. A New Companion to Digital Humanities . John Wiley & Sons, pp.251-273. ↩︎ ↩︎

Zeng, M. L. (2019). Semantic enrichment for enhancing LAM data and supporting digital humanities . <https://recyt.fecyt.es/index.php/EPI/article/view/epi.2019.ene.03/42134>. Accessed 29 April 2019. ↩︎

Beretta, F. (2017). Collaboratively Producing Interoperable Ontologies and Semantically Annotated Corpora: the symogih.org project . Third International Workshop on Semantic Web for Scientific Heritage, May 2017, Portoroz, Slovenia.

. Accessed 20 April 2019. ↩︎ ↩︎ Burrows, T. (2018). Connecting Medieval and Renaissance Manuscript Collections. Open Library of Humanities , 4(2), p.32. <http://doi.org/10.16995/olh.269>. Accessed 20 April 2019. ↩︎ ↩︎

Bellotto, A. (2017). Towards the implementation of CIDOC Conceptual Reference Model on medieval manuscript descriptions - Modelling ManusOnLine records . MA Dissertation in Digital Humanities, Faculty of Arts & Humanities, King’s College London. ↩︎

Subhashini, R. and Akilandeswari, J. (2011). A survey on ontology construction methodologies, International Journal of Enterprise Computing and Business Systems . <http://www.ijecbs.com/January2011/N5Jan2011.pdf>. Accessed 1 July 2018. ↩︎