Last Thursday, I completed the steps to deploy the 1.0 release of the Shakespeare and Company Project, updated the site index, and checked that things looked OK. It felt momentous, but I wasn’t up to tweeting about it (other than a joke about how quickly I would need a hotfix). I’m grateful to my colleague Rebecca Munson for her twitter thread talking about this moment. I also felt emotional, but in ways that made it difficult for me to want to tweet about it.

I was tired, excited, and anxious. Tired, because I had been working (along with the rest of the project team) very hard, with incredible intensity, for the past few weeks. Excited, because it is a thrill to share something like this with the world and see what people think of your work, and what amazing things they will find. Anxious, because if something goes wrong or is broken, it would likely be my fault (or at least, that’s how it feels at this moment). As technical lead on the project and lead developer at the Center for Digital Humanities, I am ultimately the one responsible for the technical choices and infrastructure. Our work is very collaborative, and there are multiple steps where work is reviewed and tested by a number of different people — unit tests, code review, acceptance testing, etc. This is reassuring, but we all know that bugs can still slip through into production uncaught.

It’s unusual to have project publicity like we’d had (featured on LitHub, an article in Princeton Alumni Weekly) — at any point on a DH project, much less as we were wrapping our 1.0 release! We always knew this project would have a much wider audience than the other projects I’ve been involved at since I joined CDH (Princeton Prosody Archive and Derrida’s Margins are admittedly rather niche). In fact, we were testing and releasing a hotfix (to correct an error in the lending library cards order that was introduced in the 1.0 release) shortly before an article about the Project was published in The Guardian.

Project data is an additional point of anxiety for me. The data for this project has been in my care for the last few years. I’m well aware of the problems that software can introduce into research data, because I’ve written about it. I handled the migrations from XML to relational database; I consulted on and helped decide many aspects of how we would track the activity in Beach’s lending library; all the large-scale scripted operations on the data were either implemented or supervised by me. Project Director Joshua Kotin is deeply involved in the project work, very familiar with the data and working with it closely — if we had introduced a problem with the data, he or one of the student researchers would probably have caught it (and they have caught and corrected many problems with the data!). But it still feels possible that there’s something I missed.

Another amazing thing about this moment was that we hit our deadline exactly as planned, which I think is probably a first for us (we’ve been close in the past; deadlines are hard!). This is a testament to the power of project management — Rebecca Munson and I took time in January, in collaboration with Joshua Kotin, to scale back the long list of features we wanted to include into something we would all be satisfied with and that could be done in the time we had. We’re aware from reading about the “planning fallacy” that reality is often worse than the “worst case” we can think of on our own — and nobody had “pandemic” in mind for a possible worst case when we planned this milestone (although we haven’t been as impacted as many).

It may have been hard for me to formulate a tweet about the release because my heart was also full. This is a massive, multiyear project and I’ve had amazing collaborators, past and present. Just check out the list of contributors and supporters on the credits page! After the 1.0 release went out, a colleague commented on how long-running this project has been and mentioned the number of babies born since it started. I joked that we should add a list of “production babies” to the credits list the way movie credits sometimes do, thinking in part of the difficulties of citation for DH projects (is it a science paper or a film?).

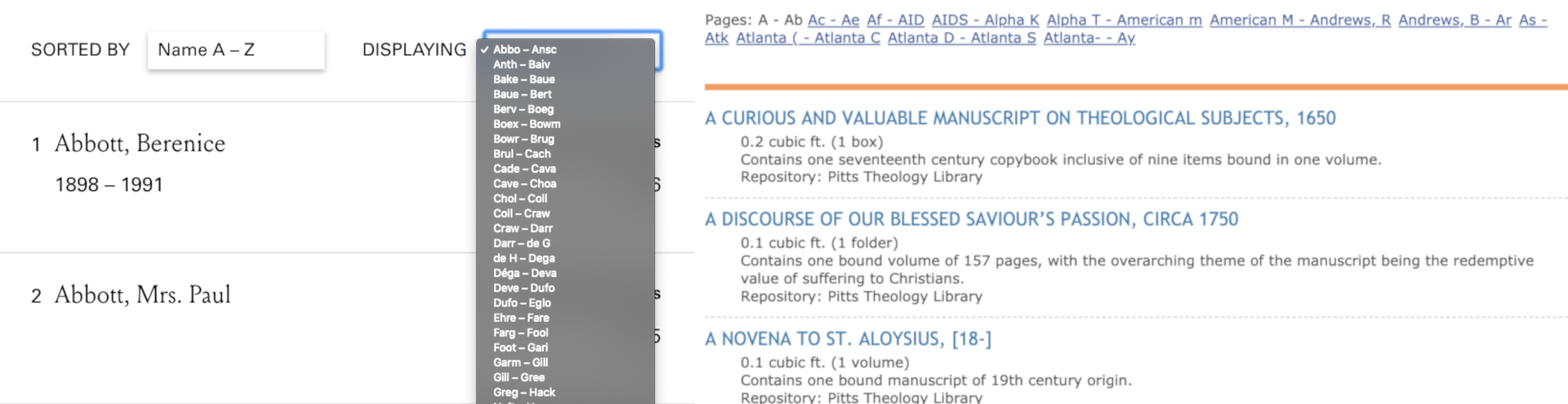

I appreciate my colleague Grant Wythoff’s twitter thread celebrating the release and providing some enticing tastes of the Project. I would love to do something similar, but any tour I can give at this point is going to be idiosyncratic. On the technical side, some of my favorite features are the little things you might not notice, and some that are not even visible. For instance, on the Members and Books pages we have standard navigation for paginated results, but we also have drop-down page navigation that lets you jump to a specific section of the results. This was a feature inspired by and adapted from the Emory Finding Aids site, which I developed in collaboration with Elizabeth Russey Roke.

I also love the way the activity tables you’ll see if you visit the site with a desktop or tablet screen display as tiles on mobile, so the same information is readable and accessible on a smaller screen.

Another thing you’re statistically unlikely to discover on your own: the site should be largely functional without JavaScript. This cost us in development time and additional complexity, and I’ve had second thoughts about it at times, but I feel strongly that things that can work without JavaScript should. It’s also important to me that as much as possible CDH project sites are stable, durable, citable objects with clean, readable, reliable URLs for content, and I think that ensuring that the site works without JavaScript (to the degree possible) helps with these goals. These concerns are at odds with the dynamic interactions that people tend to expect from web interfaces these days. I was reassured by a recent twitter thread from Sarah Withee on using the NoScript browser extension and the degree to which JavaScript breaks the basic functionality of the web, and I was reminded that this choice is not just a technical one, but a stance about how the web should work.

My tour of the content would be similarly personal. Shortly after I joined the project, Josh shared stories about some of the members related to their cards — and I remember thinking, every card has a story.1 Because of my role on the Project, I know the big picture of the data and I know all the weird corners and edge cases (because we had to figure out how to handle them). Alice Killen, the most prolific reader we have documented, was active from 1922 to 1940 with 1500 events, nearly all of them borrows! The amount of data we have for her makes the pages listing her cards and reading activity relatively slow to load, but she was such an outlier that we decided not to add pagination. Or Raphael, who we joked was a time-traveler because of a data error (long since corrected) that made it look like a library member checked a book out and took it back to the Middle Ages.

The cards for the Bernheims, which were mixed up and which Josh, Ellie Green, Nick Budak and I sorted out together (two sisters, a neighbor, and an unrelated Bernheim who was a later member). Or the lending library card for René Leibowitz, which has a collection of events for a number of other members on the reverse (figuring out how to display this card on other members’ pages was how I broke the card order that required the 1.0.1 release). I use Gertrude Stein as a frequent test case, but not for the reasons you might think — her last name occurs fully and partially in other member names (Leo Stein, Birstein, Armstein, Goldstein, etc.), and she is one of the members who has events with unknown years — a technical challenge I’ve written about previously.

A week after the release, I’m thrilled, relieved, and reassured. Thrilled by the attention the Shakespeare and Company Project has received (additional articles have appeared in El País and Le Temps) and amazed at the number of visitors to the site and continuing interest as people discover material and share their finds on Twitter. Relieved, because nothing major has broken; we’ve found minor problems, but we’re already working to correct them. Reassured, because our collaborative work and processes are doing what they should to help us develop high-quality, well-documented code that is easy to maintain. We’re continuing to work on the Project through the end of the month, because we’ve learned from past project launches that there are always unexpected changes and fixes that we’ll discover in this period. As we close this chapter, CDH staff will be taking time to reflect as a group and look back at what we’ve learned from this experience to determine together what we should take forward into new projects, and where we can do better.

My thanks to Kate Carpenter, Natalia Ermolaev, and Camey VanSant for invaluable feedback and edits, which helped clarify and improve this post.

This puts me in mind of W. S. Merwin’s poem “The Unwritten” on the potential for words and stories in a simple pencil: “every pencil in the world / is like this.” ↩︎