Software developers, like other humans, make mistakes.

There are any number of ways that errors can creep into software: from simple logic errors, or misunderstanding the needed functionality, to not accounting for the full complexity of interactions in a system in some way, to name just a few. As a simple example, when working with a record that has optional fields, the logic for interacting with and displaying that item must account for all fields being present, only the required fields, and every combination in between.

The process I’ve put in place for our CDH software development is adapted from Agile software methodologies, and to a large degree Agile is designed to combat the problem of misunderstanding what is needed. This is done by bringing the “customer” into the team and making them a part of the process. There are some ways that Agile is a good fit for the work we do here and there are other ways that it doesn’t work so well; but that’s probably a subject for another a post entirely.

There are a variety of methods and tools that help software developers find, correct, and prevent errors in the software they write. Here are some of the tools and methods we use for software development at the CDH.

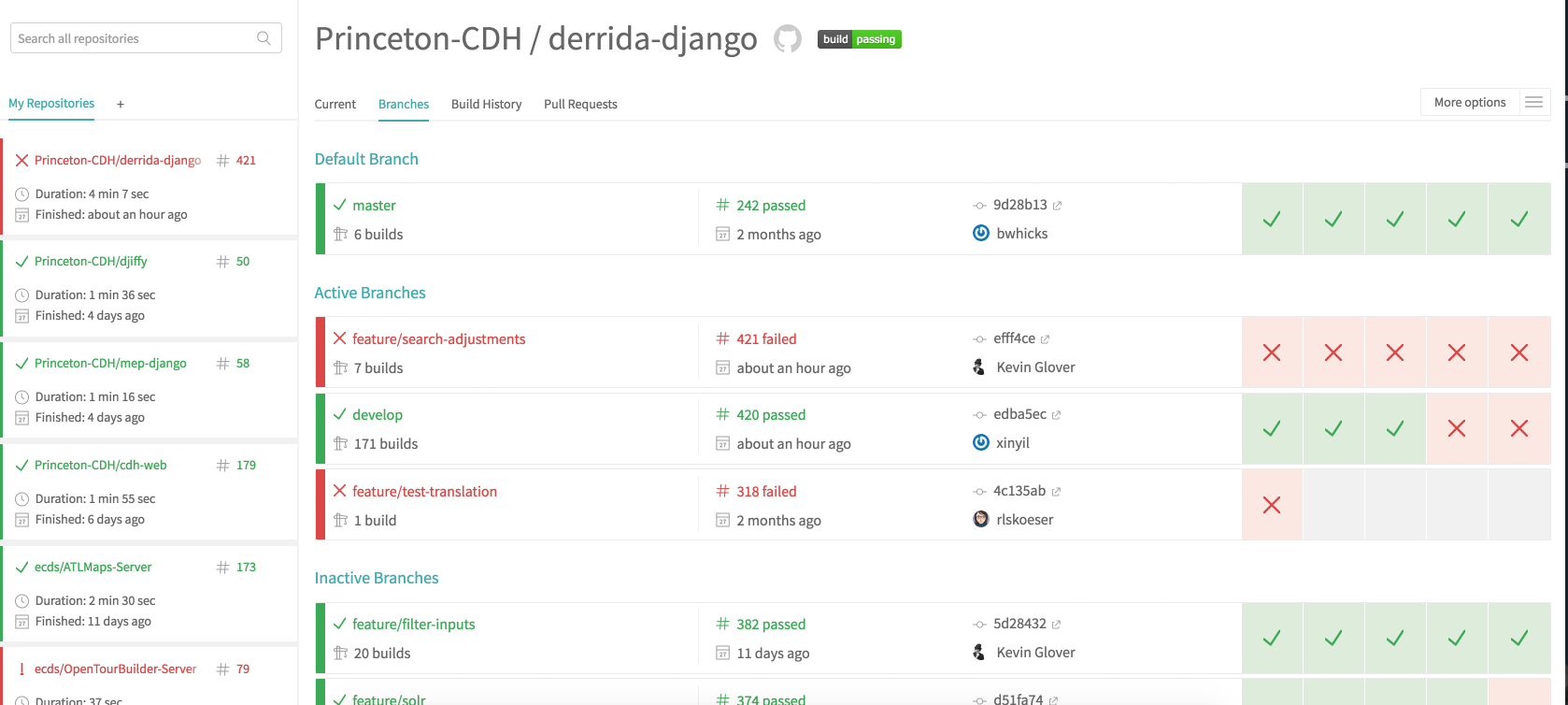

- Unit Testing. We write more code to check our code. This is done at the smallest level of code possible (hence “unit”), e.g. a single function call or method. In tests, we can run the code with different sample input or simulate errors and check that the code operates properly under different conditions. Tests are aggregated into a test suite that can be run by any developer working on the project and in an automatic fashion by continuous integration server.

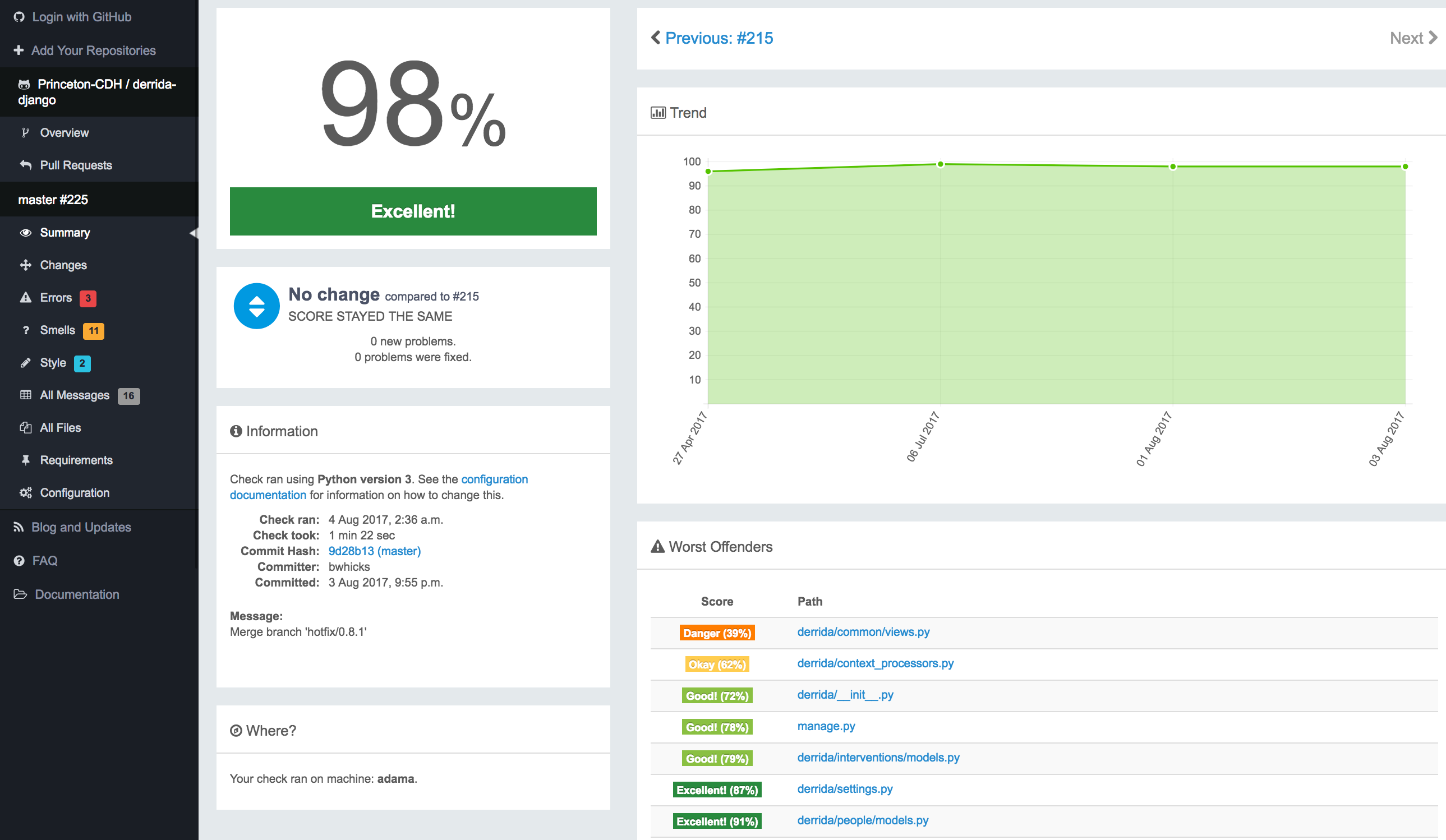

- Sometimes our automated tests also include integration tests, which check how the software interacts with other systems (such as a database or a text indexing tool). Some developers use a process called test-driven development, where they write the test first, run it to see that it fails, and then write the code to make the test pass. Sometimes the development team at the CDH will use this process to handle a bug: write test code that identifies and isolates the faulty behavior, make sure it fails, then fix the problem and check that the test passes. Unit testing can be combined with code coverage tools, which report on which parts of the code are run or not run when the tests are processed.

- Acceptance Testing. A project team member who is not a developer goes through a list of features that the developers have marked as ready for testing and checks to see if they work or not. If something doesn’t work properly, they provide feedback to the developer and it can be corrected so the functionality is acceptable. We recently went through this process for our new CDH website; Rebecca Munson, Mary Naydan, and Kate Clairmont tested the website features and, along the way, created new documentation to provide our sponsored project teams with guidance for this process. It’s incredibly valuable to have a someone else look at the system, especially a content expert look at a system; in recent acceptance testing on our Derrida’s Margins project, Katie Chenoweth recognized problems that weren’t obvious to me because I’m not familiar with the material the way she is. But once she told me about the problem, I was able to go back to the code and figure out what I missed.

- Usability Testing is a set of methods for discovering how real users interact with a system. It can be done before any software is written, using paper prototypes or mockups so that problems in a design or interface can be caught and addressed before they are implemented. This is not yet a regular part of our process for software development at the CDH, but our upcoming work on Princeton Prosody Archive includes a plan for usability testing and I’m looking forward to seeing what we learn and how it informs the project.

There are many other methods designed to improve the quality of the software. The Princeton University Library software developers use a code review process that requires a different developer to look over code changes and approve them before they are merged into the main the codebase. Another method is pair programming, where two developers work on the same feature at the same time, usually sharing a single screen; the idea is to prevent errors when the code is written instead of finding them later. This can be a way to share knowledge, and is a tool we occasionally use here at the CDH; I also think it makes a better interview exercise than asking for context-less pseudocode on a whiteboard. There are also automated tools for scanning and “linting” software to check style and “code health”; but they can only catch so much, and they aren’t available for every system or language.

In a way, all of these tools and methods are about getting more eyes on the code or the running software - whether actual, human eyes looking at a screen or automated, algorithmic eyes designed by another programmer looking at bits of code.

If a software developer like me asks you to test something for us, it’s not that we’re lazy or working too fast (although sometimes that’s true), or that we want you to do our work for us - developers test what they’re doing as they go, but we still inevitably miss things! We need another set of eyes and a different perspective to help ensure the time and energy we’re putting into developing software results in something useful.