What follow is a poster proposal for the 2013 Digital Humanities conference that Brian Croxall and I wrote as project manager and lead scholar/developer, respectively. Our fingers are crossed, and we’ll know more around 1 February 2013.

Networking the Belfast Group through the Automated Semantic Enhancement of Existing Digital Content#

There is increasing work on and interest in social networks in the digital humanities community (Meeks 2011). Analysis is frequently done on digital content—including images (Akdag Salah et al. 2012); email (Hangal et al. 2012); and citation networks (Visconti 2012)—because the data lend themselves to aggregation, conversion, and analysis. Yet despite this flurry of activity, the possibility exists for an exponential jump in network analysis. After all, the holdings and catalogs of galleries, libraries, archives, and museums (GLAMs) include traces of vast paper-based networks, but the data are locked away in forms that don’t easily lend themselves to analysis. What if we could open up that content? In this poster, we will report on an attempt to provide tools for archivists to expose the information embedded in the descriptions of their collections as well as a test case for analyzing that data: an examination of the networks of the Irish poets collectively known as “the Belfast Group.” Our goal is to develop software tools and design a workflow to enhance TEI and EAD—documents that are already commonly created and maintained by archivists and text centers—without radically increasing the time and effort involved. The software tools (http://github.com/emory-libraries-disc/name-dropper) consist of a plugin for the Oxygen XML editor and command line scripts that will, first, make use of DBPedia Spotlight to identify and annotate recognized names and other resources within the text and, second, connect to linked-data systems (starting with the Virtual International Authority File [VIAF]) to provide authoritative, scholarly identifiers. The scripts will allow technical users to inspect and tune the results or to automatically tag high-certainty resources, and the plugin will provide a user-friendly interface to review and accept suggested names while editing a document. The enhanced documents should provide significant benefits to GLAMs, allowing them to connect disparate types of content (e.g., digitized texts or photographs from an archival collection) and augment with data from other linked data systems. Furthermore, the enhanced documents will make it possible to expose these data in more machine-readable and research accessible formats. Our tools and workflow could be applied to resources held by different archives (for a different approach, see Blanke et al. 2012). What’s more, enhancing these documents helps GLAMs provide a means for researchers to do non-consumptive, social network research on the metadata of collections that might otherwise be closed or problematic in other ways (e.g., restricted correspondence from living authors).

Although our tools are not yet complete, we have already begun preliminary visualization and analysis of network relationships using data that mirrors what we will generate automatically by Summer 2013. The difficulties of defining “the Belfast Group” make for a compelling test case for our attempt to understand networks via data that are newly machine readable. The Group is a contentious network since the label has been variously applied to a weekly writing workshop that ran from 1963-1972, the most famous poets who attended that workshop—including Seamus Heaney, Michael Longley, and Paul Muldoon—or more loosely applied to all of the writers who “put Belfast on the literary map” (Clark 6). The significance of the writing workshop is debated by critics and often rejected by the poets themselves, sometimes vehemently. In contrast to a more formalized group, some scholars identify “an informal community” of poets evidenced by their letters, promotion of each other, and poems dedicated to each other (Drummond 32), connections which are richly documented by archival materials held at Emory University.

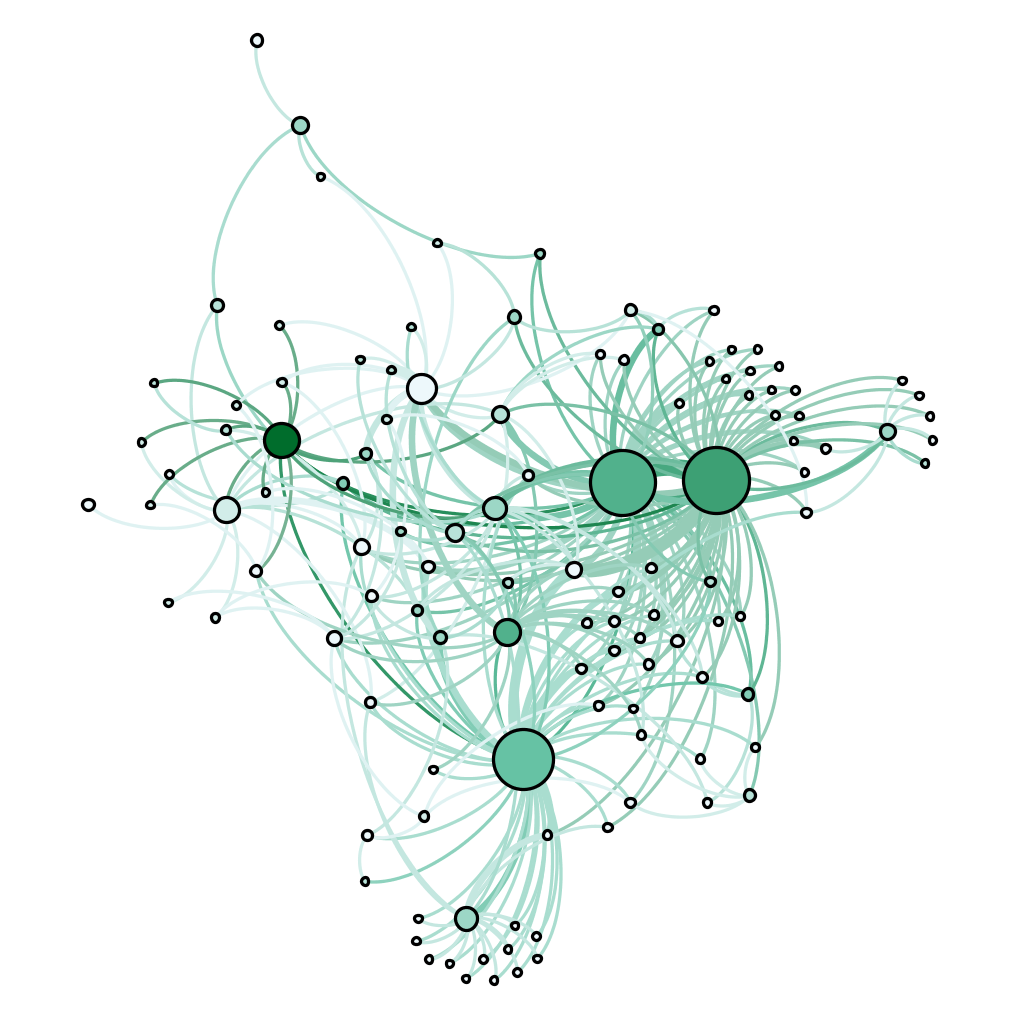

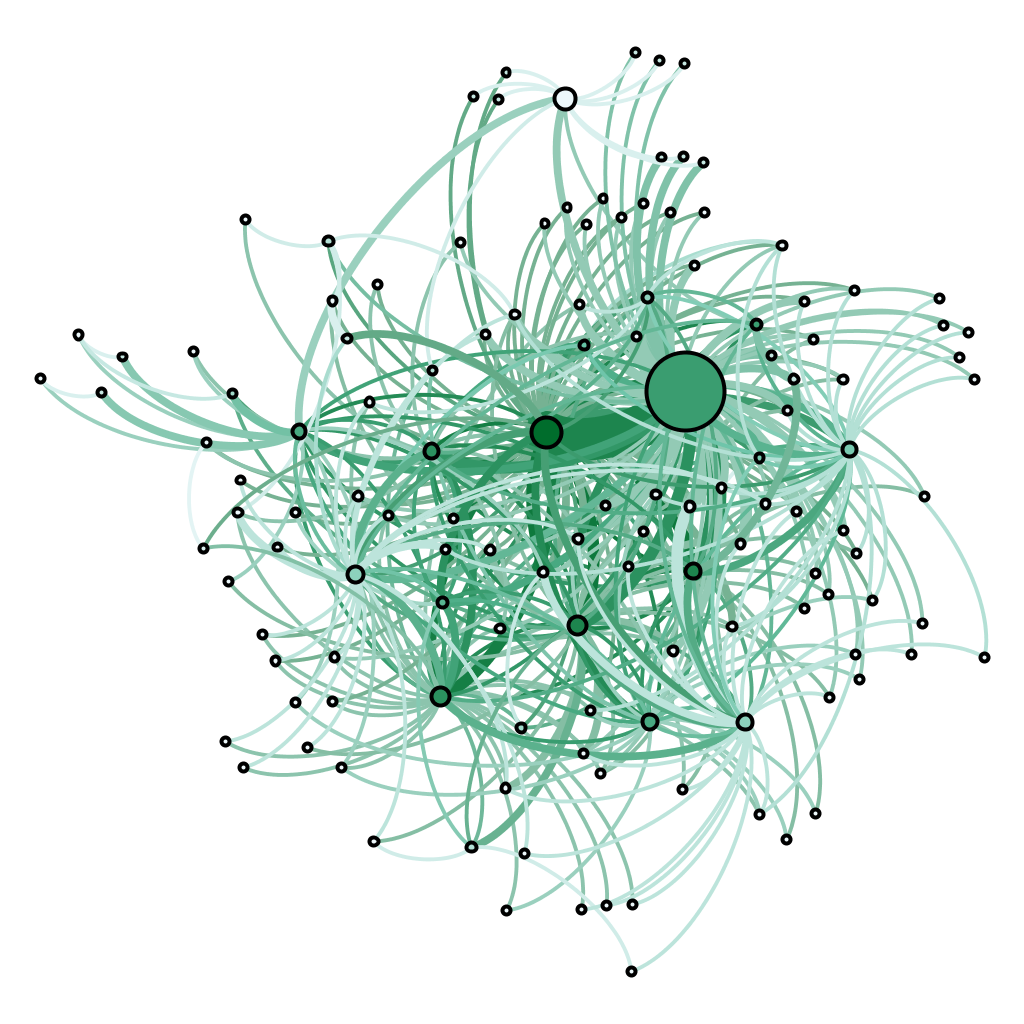

Using preliminary data manually generated from a subset of the correspondence EAD, our data suggests a wider set of connections in the Group than traditional scholarly approaches. The latter selectively emphasize the relationships of the most prominent authors and the role of the writing workshop (see fig. 1). Since our data is based on a much larger set of artifacts, as well as their complete metadata, we find that the locus of poetic activity in Belfast is not so oriented around the workshop (see fig. 2). Once we collect the full dataset via our completed tools and workflow, we will compare it with models generated by traditional scholarly methods, to identify significant gaps and discrepancies in either model.

Providing not only this new analysis of the Belfast Group’s network and a report on the development of our tools, our poster presentation at DH 2013 will also include a hands-on demonstration of the software tools and interactive visualizations of network data.

References#

- Akdag Salah, Alkim Almila et al. “Exploring Originality in User-Generated Content with Network and Image Analysis Tools.” Digital Humanities 2012. University of Hamburg. 19 July 2012.

- Blanke, Tobias et al. “Information Extraction on Noisy Texts for Historical Research.” Digital Humanities 2012. University of Hamburg. 19 July 2012.

- Clark, Heather. The Ulster Renaissance: Poetry in Belfast, 1962-1972. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

- Drummond, Gavin. “The Difficulty of We: The Epistolary Poems of Michael Longley and Derek Mahon.” The Yearbook of English Studies, Vol. 35, Irish Writing since 1950 (2005), pp. 31-42

- Hangal, Sudheendra. “Processing Email Archives in Special Collections.” Digital Humanities 2012. University of Hamburg. 20 July 2012.

- Litta Modignani Picozzi, Eleonora, Jamie Norrish, and Jose Miguel Monteiro Vieira. “Complex entity management through EATS: the case of the Gascon Rolls Project.” Digital Humanities 2012. University of Hamburg. 18 July 2012.

- Moretti, Franco et al. “Networks, Literature, Culture.” Digital Humanities 2011. Stanford University. 21 June 2011.

- Meeks, Elijah. “More Networks in the Humanities or Did books have DNA?” Digital Humanities Specialist. 6 December 2011. Web. 1 November 2012. https://dhs.stanford.edu/visualization/more-networks/.

- Mendes, Pablo N. et al. “DBpedia Spotlight: Shedding Light on the Web of Documents.” Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Semantic Systems (I-Semantics). Graz, Austria. 7–9 September 2011. http://www.wiwiss.fu-berlin.de/en/institute/pwo/bizer/research/ publications/Mendes-Jakob-GarciaSilva-Bizer-DBpediaSpotlight-ISEM2011.pdf.

- Pitti, Daniel, et al. “The Social Networks and ARchival Context Project.” Digital Humanities 2011 Stanford University. 22 June 2011.

- Pitti, Daniel, et al. SNAC: The Social Networks and Archival Context Project. Web. 29 October 2012. http://socialarchive.iath.virginia.edu/.

- Visconti, Amanda. View DHQ: Citation Network Visualization for Digital Humanities Quarterly. Web. 1 November 2012. http://digitalliterature.net/viewDHQ/