This session consisted of a presentation on an approach for multi-modal analysis to compare text, video and subtitles for different representations of the same story; another on automated analysis of emotional affect in user-tagged images; and a third presentation an a process for doing aural analysis on digital texts.

“Eric, you do not humble well”: The Image of the Modern Vampire in Text and on Screen#

Lisa Opas-Hanninen (view abstract, video of the presentation

This project was inspired by student interest in studying TV and popular culture, combined with the limited availability of concordance tools with multi-modal support. The choice of vampires as a topic was sort of “by the way,” and they could have done this with plenty of other things, but it’s an interesting topic because of their increasing popularity since Anne Rice and the progression to representing them as more human and emotional, but still dangerous, like a modern-day Heathcliff. For this project they focused on the image of Eric in “True Blood”, looking at both the Sookie Stackhouse book series and the TV series. They started with CATMA, as a nice kind of concordance tool, and then they modified it to add multimodal support, creating a new tool they are calling “LICHEN.” They aligned subtitle files with videos by time-stamp (which is easy if the subtitles are extracted from the video), and then built a bridging tool to link scenes from the book to scenes in the TV series. The basic logic for this bridging tool was to divide the novel into paragraphs and use rare n-grams to guess at linkages; for example, if a trigram appears only once in the novel and once in the subtitles, then it’s quite likely to be a link. In addition, they marked up the text to identify descriptions of Eric so that they could look for differences between the representations in the text and in the video. The hope is that this type of approach would be applicable to any kind of multimodal study involving any combinations of text, image, and count, e.g. dialectology, conversation analysis, etc. The multi-modal version of CATMA will be made freely available; the bridging tool is still being tested.

The presentation didn’t seem to include much in the way of interpretation of their results for this particular use case with these tools, but this does seem like an interesting and promising approach. Mapping connections between different works like aso has some potential for investigating the mismatch and rearrangement of a novel to TV script. I was a little surprised they used CATMA for this; perhaps I still had OpenAnnotation on the brain from the pre-conference session I attended, but that seems like it could be a much better fit and approach, since the OpenAnnotation folks have already been working to address how to annotate particularly parts of a text or a work, and I’m pretty sure the range of annotations it accommodates would make it pretty straightforward to document different representations or versions of the same scene, and having an open, sharable dataset seems like it would be incredibly valuable, and allow for more collaboration. There was an interesting moment when the presenter was asked about working on such recent materials in copyright, and she actually didn’t seem to want to say much about how they obtained the material they were working with; it seems that annotation data about the connections between these different works would still be sharable even if the content isn’t, as long as there are ways to reference the particular parts of the content reliably, which is something I imagine is pretty important for this type of work anyway.

Feeling the View: Reading Affective Orientation of Tagged Images#

Jyi-Shane Liu (view abstract)

The motivation for this project is the huge volume of images on the web, often available with some kind of tagged description; the assumption is that those tagged images somehow capture or relate to human emotions. Starting with Russell’s Circumplex Model of Affect and 28 emotion words (which are positive or negative, and high or low intensity), they selected the three most commonly used terms from each quadrant. Liu cited research indicating that emotion is very rarely represented in Flickr tags, so his approach was to attempt to infer emotion for tagged images. Most of the tags are not in the WordNet dictionary (due to the use of typos, names, etc); so, they filtered results by user comments and feedback. To evaluate this approach, they took the list of tags for each quadrant, searched Flickr, and then ran user-testing to compare the Flickr images to Google images. The user-testing indicated that their method works better for positive high-intensity affective terms than for the positive lower-intensity terms.

I have to admit, I was not quite clear on the presented conclusions, or where the team thought their method was working better than any of the existing options; from the examples displayed during the presentation I actually thought the Google results seemed more representative of the stated emotion. I was also a bit surprised to learn that there was no actual image analysis going on here, and that all of this was purely text-based.

Sounding for Meaning: Analyzing Aural Patterns Across Digital Collections#

Tanya Clement (view abstract, video of the presentation

Alternative title for this presentation: “Using Predictive Modeling and Visual Analysis to Measure Prosody in texts by Gertrude Stein”

Clement started by explaining that they chose to look at the work of Gertrude Stein for this project because her writing has very evocative sound and language, which has been noted by fans of her work as well as scholars. Then Clement proceeded to discuss Charles Bernstein’s distinction between orality and aurality and the sound of writing. There haven’t been tools readily available for sound or recording analysis, with the exception of some small-scale hand-done projects, for example a composer graphing sound. Clement mentioned previous Digital Humanities phonetic and symbolic work, such as AnalysePoem and PatternFinder, but says in this case they are working with the “surrogate of sound” or pre-speech.

Their process is to use ProseVis with SEASR; upload a TEI file and use OpenMary to annotate aspects of speech such as part of speech, accent, phoneme, tone, break index, using a “best guess” algorithm based on how humans speak, parts of speech, etc. They use SEASR for workflow and pre-processing; OpenMary is applied at the paragraph-level, which Clement admits has some conflict with lines of poetry. This process generates a detailed tabular output, but since that is a very difficult way to read something, they map it back to the text.

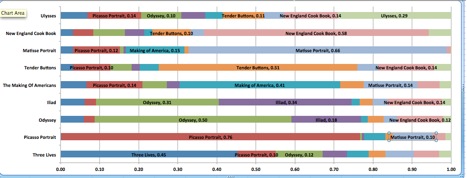

One application of this aural analysis is to do predictive modeling based on what texts sound like other texts. There is a notion that Stein’s Tender Buttons sounds like a cookbook, written in a style that is a kind of rejection of “high culture”; the current version of the predictive modeling is not great, but it does indicate that Tender Buttons was closest to a cookbook from the same time period, and the Iliad and the Odyssey were most similar to each other.

Clement closed by noting that we’re pretty good at working with text, but not so much with sound, image, or video, and said that one possible next step in this project will be to start looking at archival sound files.

There audience at this session was quite interested in this project, and there were a number of questions. Syd Bauman wanted to know if this process can makes use of stress (which makes me wonder if it could be applied to inferring poetic rhythm or meter); someone asked about regional dialects and pronunciations, and Clement explained that OpenMary uses the CMU pronunciation dictionary, but also has artificial intelligence that attempts to “sound out” words it doesn’t know. Another respondent said that this approach is “sketchy” because the tools being used were designed for Natural Language Programming; the results are interesting, but can we really consider it to be sound or aural? Clement explained that this goes back to her notion of the “surrogate of sound,” and that this approach is looking at the sounds as they have the potential to be heard based on structure and syntax, not an actual speech performance. David Hoover pointed out that the type of color-based visualization they are currently using is problematic because the patterns you notice depend on the colors you choose; Clement noted that the tool does allow for customizing the color palette, which at last partially addresses Hoover’s concern, and also commented that there is an additional problem with the current visualizations, because there aren’t as many distinguishable colors as there are features they want to look at.